Don't Ban AI. Redesign Instruction.

Why the real opportunity isn’t to restrict artificial intelligence—but to raise the floor on learning

Join our nearly 9,000 subscribers by clicking below and becoming a subscriber. Consider becoming a paid subscriber to support the work of Educating AI.

Schools have increasingly responded to AI by blocking frontier models while providing access to educational AI platforms. Teachers have updated syllabi with AI-use policies tied to these approved tools, and detection technology has advanced as companies like Google and Grammarly expand process monitoring capabilities. Yet our assessment methods remain largely unchanged—or in some cases have regressed, as educators either rely on AI to design evaluations or retreat to handwritten, in-person testing.

These responses reflect the immense pressure teachers face during this period of technological disruption. However, I've grown convinced that blocking, detecting, monitoring, or circumventing AI represents an inadequate response to the scale of change we're experiencing. The transformation is too fundamental to address through fragmented measures.

AI is no longer something we can keep "out there." It's already in students' browsers, personal devices, writing, and thinking routines. And that's not necessarily a bad thing.

What's more dangerous than AI is continuing to assign learning tasks that are so predictable, so interchangeable, so lifeless—that a machine can do them just as well as a student.

Instead of trying to restrict AI, we need to outgrow the kinds of tasks it replaces.

From Restriction to Redesign

When calculators first entered schools, many teachers worried students would never learn math facts again. When spellcheck appeared, there were concerns students would lose the ability to proofread. In both cases, we adjusted—not by banning the tools forever, but by raising our expectations of what students should do.

This is that moment for AI. But it's more complicated.

AI doesn't just speed up a task—it can generate the entire thing. A chatbot can simulate voice, structure, tone, even "mistakes" in student writing. So if we want to avoid becoming a generation of educators locked in an endless game of AI detection and discipline, we need a better strategy.

We don't need more fear. We need more purpose.

What Kind of Learning Do We Want?

This question—though it might sound lofty—is practical and urgent.

If we want students to be ethical, critical, adaptive thinkers in a world with AI, then we need to stop organizing schools around what machines do better than humans.

This means letting go of certain habits that have long dominated instruction:

Coverage over inquiry

Product over process

Speed over depth

Answers over ambiguity

We're not saying this is easy. But we are saying it's necessary—and we believe it's possible.

Rethinking the Goal: What AI Can and Can't Do

Let's begin with a simple framing:

What AI Can and Can't Do in the Classroom

AI excels at completing traditional school tasks when they're isolated and formulaic. It can generate essays on demand, solve textbook problems, create presentations with polished visuals, and produce research summaries that sound authoritative.

But AI struggles with sustained intellectual work that unfolds over time—tasks that require building relationships, navigating real constraints, iterating through genuine confusion, or making judgment calls that depend on lived experience and evolving context.

The work ahead isn't to avoid AI—it's to design learning experiences that require the kind of sophisticated judgment, contextual reasoning, and iterative collaboration that comes from working with these tools thoughtfully rather than defaulting to them automatically.

That means giving students opportunities to:

Take positions that matter

Investigate ideas they can't Google

Work through messy drafts and revision cycles

Communicate to real audiences

Solve problems in real time, with real constraints

This is the work that requires genuine intellectual engagement. And this is where school must go.

The Graduate Profile: A New Compass for an AI World

What should guide instruction in a world where information is everywhere, and automation is instant?

The answer can take the form of a clear, actionable Graduate Profile—not a vision statement, but a concrete set of capacities that should be strengthened across the K–12 journey.

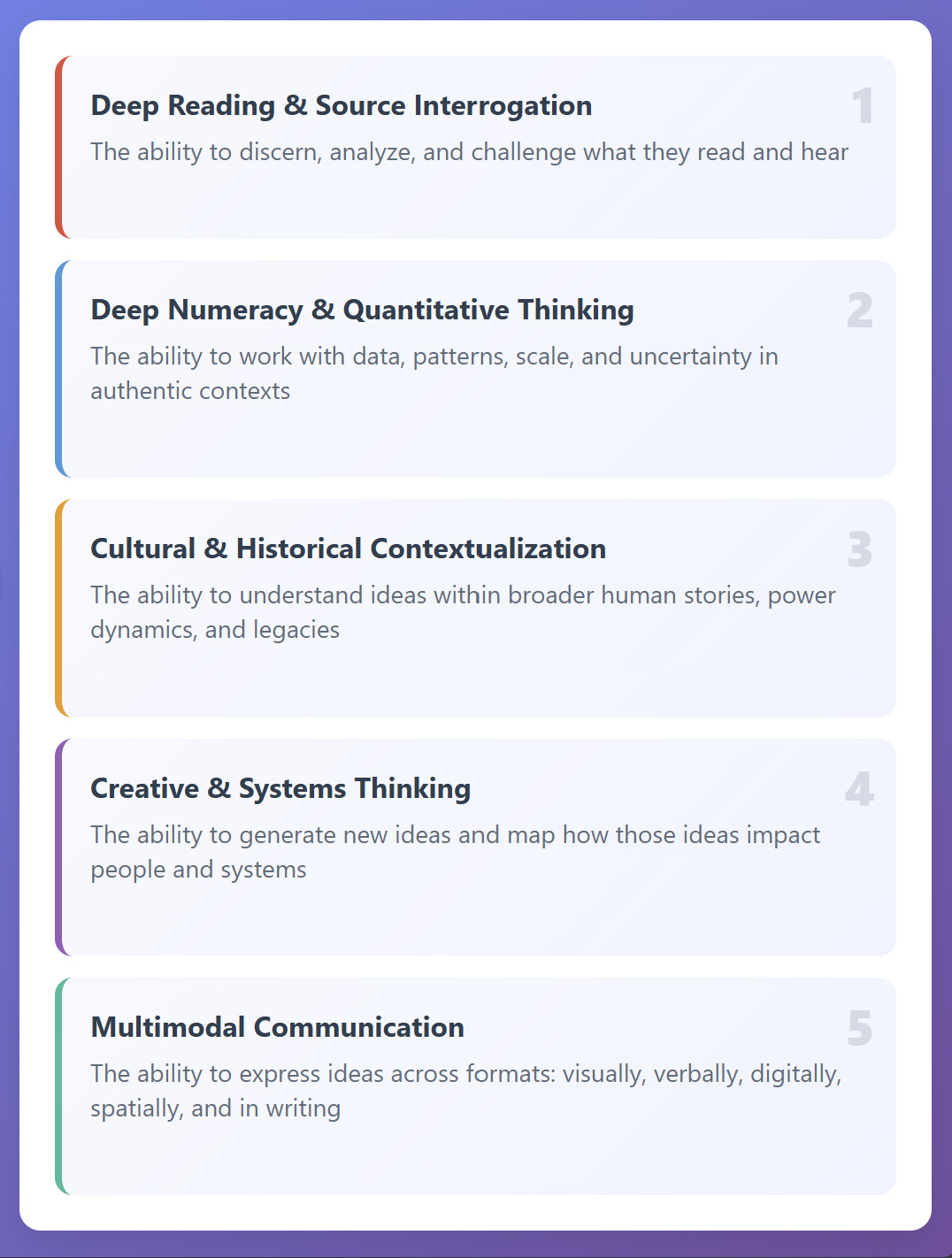

Here are the five competencies we believe every student needs:

Deep Reading & Source Interrogation → The ability to discern, analyze, and challenge what they read and hear

Deep Numeracy & Quantitative Thinking → The ability to work with data, patterns, scale, and uncertainty in authentic contexts

Cultural & Historical Contextualization → The ability to understand ideas within broader human stories, power dynamics, and legacies

Creative & Systems Thinking → The ability to generate new ideas and map how those ideas impact people and systems

Multimodal Communication → The ability to express ideas across formats: visually, verbally, digitally, spatially, and in writing

These competencies require the kind of sustained engagement, contextual judgment, and iterative refinement that benefits from AI collaboration rather than AI replacement. They're difficult to fake because they demand authentic intellectual work over time. When someone is deeply engaged in these processes, we sense their genuine involvement and developing expertise. Therefore, regardless of technological advances, future-ready schools must prioritize these capacities above all else.

The challenge lies in keeping students engaged with these competencies even as they gain access to increasingly sophisticated AI tools.

What Changes in the Classroom?

We often get asked: "What does this look like in practice?" Here's a before-and-after example to illustrate the shift:

BEFORE – 9th Grade World History

Read textbook pages on the Industrial Revolution

Complete guided notes

Write a short essay answering: "Was the Industrial Revolution more helpful or harmful?"

AI Risk Level: High. A chatbot can do this in seconds.

AFTER – AI-Resilient Redesign

Students visit a local factory or trade museum

Interview a worker or tour guide about the legacy of industrialization

Build a multimodal exhibit with artifacts, sound, and image

Host a "Factory Futures" gallery walk with invited guests

Reflect on how AI could both revive and threaten blue-collar industries

AI Role: Supplement—not substitute. Students might use AI to simulate historical voices, generate timelines, or fact-check—but the core of the work is personal, physical, contextual.

The goal isn't to eliminate AI. It's to design the task so AI can enhance, but not complete, the work on its own.

But let's be honest: this is not a fixed line. What seems AI-resistant today may become routine tomorrow. The boundaries are porous, and they shift with each new model release. That's why the real work isn't finding tasks that only humans can do—it's creating instruction where AI as currently developed doesn't overshadow student agency, and where using these tools becomes an avenue for deeper engagement with the competencies we value.

This means we need to test our assumptions constantly through classroom practice. Does this assignment still require genuine engagement and thinking when students have access to the latest AI? Are students using these tools to deepen their understanding or to bypass it? The answers will keep changing, and so must our approach.

Three Practical Moves for Schools

You don't need to overhaul your curriculum overnight. Here are three concrete steps to start with:

1. Audit a Task with a New Lens

Take one assignment from last semester. Ask:

"Could a chatbot complete this without the student doing any real thinking?"

If the answer is yes, think about how to add:

A real audience or authentic context

A live performance or collaborative element

A requirement to document learning steps, not just submit a product

2. Name the Capacity Being Developed

For every assignment, ask:

"What intellectual capacity is this helping students strengthen?"

Make that skill visible in your rubric and in your classroom conversations. Students need to know what they're practicing—and why it matters. Then ask the follow-up: "How might AI use either support or undermine this development?" Adjust accordingly.

3. Design With Students, Not Just For Them

Bring students into the conversation. Ask:

Where do you feel most engaged in class?

Where do you use AI already—and what helps you use it well?

What kinds of learning feel meaningful, memorable, or real?

Their answers can guide better design than any list of tools ever will.

Final Thought: This Is Our Moment

AI is here. There's no use pretending otherwise. But the opportunity in front of us is not just to adapt—it's to lead.

This is our chance to raise the floor and the ceiling of what learning can be. To stop organizing school around task completion, and start organizing it around intellectual development. To design learning that asks students to think more deeply and act more purposefully—whether they're working independently, collaboratively, or in partnership with AI systems.

Because in a world where these tools can do so much, it's the quality of thinking, judgment, and purpose we bring to using them that matters most.

Nick Potkalitsky, Ph.D.

Next in this series: "Could ChatGPT Do This Overnight?" If Yes, Redesign It. I’ll walk you through a six-filter tool that helps teachers and teams reimagine instructional tasks—so they're not only AI-resistant, but purpose-rich and intellectually demanding.

Check out some of our favorite Substacks:

Mike Kentz’s AI EduPathways: Insights from one of our most insightful, creative, and eloquent AI educators in the business!!!

Terry Underwood’s Learning to Read, Reading to Learn: The most penetrating investigation of the intersections between compositional theory, literacy studies, and AI on the internet!!!

Suzi’s When Life Gives You AI: A cutting-edge exploration of the intersection among computer science, neuroscience, and philosophy

Alejandro Piad Morffis’s The Computerist Journal: Unmatched investigations into coding, machine learning, computational theory, and practical AI applications

Michael Woudenberg’s Polymathic Being: Polymathic wisdom brought to you every Sunday morning with your first cup of coffee

Rob Nelson’s AI Log: Incredibly deep and insightful essay about AI’s impact on higher ed, society, and culture.

Michael Spencer’s AI Supremacy: The most comprehensive and current analysis of AI news and trends, featuring numerous intriguing guest posts

Daniel Bashir’s The Gradient Podcast: The top interviews with leading AI experts, researchers, developers, and linguists.

Daniel Nest’s Why Try AI?: The most amazing updates on AI tools and techniques

Jason Gulya’s The AI Edventure: An important exploration of cutting-edge innovations in AI-responsive curriculum and pedagogy.

Yes, you raise good questions. In many ways, we have few examples of the kind of work I am trying to characterize. My instances are placeholders that can and should be picked apart by other skillful instructors like yourself. I also am very partial to the intellectual labor of an essay. Multimodality is perhaps a way of preserving or repositioning that labor in a meaningful way in these AI altered circumstances. So much of this deeper work involves building trust and a shared vision with our students. Following their interests to spaces of genuine skill and knowledge development. The path is definitely not clear.

The fact that LLMs can produce essays on demand, answer questions based on a reading, summarize, generate authoritative-sounding research summaries, etc.doesn’t mean that these tasks are not useful for learning. They are in fact very likely to lead to learning when completed by a human. The “deep learning” field trips sound wonderful and appealing, but there are many ways in which they are unlikely to lead to actual learning. Also, spell check and calculators can and do indeed lead to poor spelling and lack of automaticity with math facts, both of which impede the higher order thinking and learning that we all want.