Laying a Foundation: Portfolio Assessment in the Context of AI-Enabled Writing Instruction

Guest Post by Terry Underwood from Learning to Read, Reading to Learn

Greetings, Dear Readers,

Before I begin, I want to thank my readers who have decided to support my Substack via paid subscriptions. I appreciate this vote of confidence. Your contributions allow me to dedicate more time to research, writing, and building Educating AI's network of contributors, resources, and materials.

In late December, I had the pleasure of crossing paths with Terry Underwood, a reader of my newsletter Educating AI and Professor of Curriculum and Instruction as California State University-Sacramento. What began as a simple reader-writer interaction quickly blossomed into a mentorship that has profoundly influenced my understanding of writing curriculum, assessment, and grading. Through our dialogues, a crucial insight emerged: AI itself is not the primary obstacle in revolutionizing writing education. Rather, it's what Terry aptly calls "the hamburger method" of teacher writing—a formulaic approach that has dominated U.S. classrooms for over three decades.

Under Terry's mentorship, I've begun to explore a methodology that is student-oriented, craft-focused, and feedback-driven. This approach seeks to break free from the constraints of preset objectives, rigid outlines, inflexible assessment criteria, and traditional grading scales. Our conversations have naturally gravitated towards the concept of portfolios as a flexible, comprehensive way to guide instruction and assess student growth over time.

At this juncture, I'm thrilled to hand the floor over to Terry, an international expert in portfolio design and implementation. His expertise seamlessly blends traditional educational methods with cutting-edge AI implementation, particularly in its application as a reading technology and writing tool. This unique combination of knowledge positions Terry at the forefront of innovative educational practices. In a follow-up article, he will delve deeper into the relationship between grading and portfolios, as well as explore grading practices on a more abstract level.

I'm confident that our readers are in for an enlightening journey as we explore these innovative approaches to writing instruction and assessment. Terry's wealth of experience and forward-thinking perspective are sure to provide fresh insights for educators navigating the intersection of traditional teaching methods and emerging AI technologies.

Terry’s Credentials:

Member of the design team 1991-1994 creating a template for a statewide on demand authentic assessment of aesthetic reading in California, an assessment that was implemented for one year and then defunded by a conservative governor. Soon the winter of NCLB happened followed by CCSS. Authentic assessment went in the deep freeze.

Member of the design team creating the New Standards Projector platform (1991-1996) for assessing English-Language Arts in middle and high school via portfolio. I was contracted to write the portfolio handbook students in 19 states would read as a manual for constructing NSP materials for scoring at a national moderation session.

Consultant for Iowa to write feedback for teachers across the state documenting evidence from their practice using teaching portfolios (early 1990s).

Doctoral dissertation on a study of a portfolio system in a California middle school (1996) mentored by Sandra Murphy, David Pearson, and Carl Spring.

Promising Researcher Award from NCTE (1996) based on a 50-page limit paper summarizing my dissertation selected by a panel reading anonymous papers (my most satisfying moment:).

Publication of a book (1998) from my dissertation by NCTE aimed at a practitioner audience presenting the qualitative narrative from my mixed methods project.

Publication of a book with Sandy Murphy (2000) on portfolio frameworks documented with hard-to-find materials (rubrics, tasks, etc.) at the classroom, school, state, and national levels.

Member of the design team creating a portfolio template and rubric system for PACT, Performance Assessment for California Teachers (2002). I served as a trainer-of-trainers to equip regional scoring centers to use portfolios documenting "teaching events" in correlational harmony with scores on local "signature assignments." This system went on to be the foundation of a national teacher performance portfolio template.

Designed and implemented a portfolio assessment system with the Language and Literacy Graduate Area Group Reading Specialist Credential faculty at CSU Sacramento (2002 forward). I used the system template to increase curricular coherence vis a vis "signature assignments" embedded in one selected course parallel with the content requirements of the California Commission on Teacher Credentialing.

Teacher of a Freshman Experience course built on an electronic portfolio platform according to design specifications I created. This design was a failure both in implementation and in take-up. In my opinion, it failed because of the rigid faculty silos dotting the intellectual landscape of the statewide university system in relation to resources.

Principle assessment consultant to faculty writing teams for the Western Interstate Academic Passport in Education (WICHE) project. WICHE set out to write rubrics for a cluster of universal learning outcomes at the baccalaureate level (cf: VALUE rubrics at AACU) to serve as the basis for interstate agreements about community college student transfer without credit audits based on a "trust but verify" strategy (2013-2015).

Team member to write the VALUE rubric on reading in college mentored by Susan Albertine (2009).

“Public and private leaders and assessment experts must ensure that assessment of writing competence is fair and authentic. Standards, curriculum, and assessment must be aligned, in writing and elsewhere in the curriculum, in reality as well as in rhetoric. Assessments of student writing must go beyond multiple-choice, machine-scorable items. Assessment should provide students with adequate time to write and should require students to actually create a piece of prose. Best practice in assessment should be more widely replicated” ‘The Neglected R’ (The National Commission on Writing in America’s Schools and Colleges, 2003)

The complete title of the ‘Neglected R’ report (2003) from two decades ago includes this phrase: “The Need for a Writing Revolution.” If the intervening years have produced such a revolution, I haven’t seen it. During several decades before ‘The Neglected R’ sounded the alarm, research exploded with new insights into how people write and how to teach them, relying on introspection, document analysis, think-aloud, interviews, observation, and related methods. These methods were crucial because the bottom-line question on the cutting edge of theory had changed profoundly along with the unit of analysis. Prior to the 1960s, those working as researchers wanted to understand how texts work. The renaissance in theory commencing in the 1960s meant pivoting from questions about how texts work to questions about how writers work. Answers could be found not in studying texts, but in studying writers.

The term "portfolio" had no situated, shared meaning in formal schooling before the 1980s when writing teachers began to question the ontological validity of product-based evaluation. Grounded in this paradigm shift from ‘writings’ to ‘writers,’ the public recognition of portfolios as a strategy to improve learning produced a rich new genre of well-regarded and influential papers, monographs, and books. Janet Emig (1977) published a seminal piece in College Composition and Communication titled “Writing as a Mode of Learning,” proposing that “…writing uniquely corresponds to certain learning strategies” (p.122) and that “…the losses to learners of not writing are compelling…[and without instructional change] writing itself as a central academic process may not long endure” (p.129).

Part of the situation Emig found herself in was complicated by a new sociopolitical context regarding going to college. During the years following WWII, more and more people from low socioeconomic groups began attending college. The 1960s marked the construction of community college campuses across the country to accommodate the growing college population. A new breed of student emerged during this period, a category that Sondra Perl “unskilled college writers” and Mike Rose called “basic writers.” Perl noted the following conclusion in her study published in 1979 in Research in the Teaching of English titled “The Composing Processes of Unskilled Writing,” a study building on the earlier research of Mina Shaughnessy:

“Indeed, their lack of proficiency may be attributable to the way in which premature and rigid attempts to correct and edit their work truncate the flow of composing without substantially improving the form of what they have written….Editing played a major role in the composing processes of the students in this study.”

Where would this new class of college writer have gotten the idea that writing is editing? Perl also saw a dominant perspective on writing among these students which she called “egocentricity”:

“While they occasionally indicated a concern for their readers, they more often took the reader’s understanding for granted. They did not see the necessity of making their referents explicit, of making the connections among their ideas apparent, of…relating one phenomenon to another, of placing [their thoughts] in an orienting conceptual framework.”

Perl and others painted a picture of high school graduates who do not see writing as a Emig’s “mode of learning” but as a problem of articulation and editing. It remains unclear whether teachers in schools and colleges today see writing as a mode of learning or as a skill to evaluate. Emig’s insight changed the theoretical game if not practice. Seeing writing as learning reframed the default view of writing as teaching text-making, teaching as assigning, and instruction as controlling writers such that their writing warrants “a good grade.” Beyond a doubt many teachers see grades as the primary motivation for writing.

Viewing writing assignments as opportunities for teachers to take over the executive function by spelling out the goals of the assignment and then stepping back effectively taught writing as a “mode of learned helplessness.” Assignments are opportunities to evaluate rather than opportunities to learn, and teachers believe that students will not write unless they are graded. Perl developed the concept of the "felt sense" in writing, describing the bodily experience writers have when they're trying to articulate something that's not yet clear. When the goal is to say something meaningful which is not yet clear, intention makes all the difference. Teaching writing rather than writers requires learners to adopt the intention of the teacher.

Using the word ‘writing’ in the context of what teachers are supposed to be teaching, as I’ve just done, is dangerously ambiguous. The gerund in English—verbs ending in /-ing/—is useful because this inflectional suffix also serves as a derivational suffix. As you may know, inflectional suffixes do not change the grammatical category of a verb: “I am writing about portfolio assessment” expresses an ongoing action as a verb. “You are reading my writing about this topic” changes the verb into a noun (derivational), a thing like a text. This ambiguity makes it impossible to know what teachers mean when they say “I am a teacher of writing.”

*****

To create a portfolio strategy for implementation in a classroom or a school rather than in a district or a state, I advise a year long professional development structure focused on supporting faculty in clarifying for themselves what they think they are teaching when they are teaching writing. Such development would include reading some of the seminal research between the 1960s and the 1990s as well as collaborative teacher research groups focused on collecting, sharing, and discussing “interesting failures,” examples of raw observations wherein the teacher experimented with an innovation that didn’t pan out quite the way it was expected to. Often, teacher groups learn more from what didn’t work with reflections on reasons than they learn from show-and-tell sessions.

Any individual teacher is perfectly positioned to create and use a portfolio system. At the level of a department or school, a designated portfolio coordinator with reassigned workload is essential. Here is a list of books and authors a writing instructional coordinator in a department or a school might consider purchasing for use during this first year and for reuse when new teachers join the faculty. Local portfolios for writing can fail badly if teachers haven’t availed themselves of the seminal work that was done before the great NCLB freeze.

James Britton—A British researcher whose work on language and learning greatly influenced writing instruction in the United States, Britton was a key figure in the London School, a group of educators and researchers who revolutionized the teaching of English in the UK during the 1960s and 1970s. Akin to Emig’s concept of writing as a mode of learning, Britton wrote about the crucial role of language in learning across all subjects, not just in English classes. His book "Language and Learning" (1970) explored the relationship between language and thought in education. Britton proposed three main categories of writing: transactional (informative), expressive, and poetic, with deep implications for portfolio assessment.

Peter Elbow—Known for his work on freewriting and his influential books "Writing Without Teachers" (1973) and "Writing With Power" (1981). Elbow wrote about our two “writing muscles,” the bicep and the tricep. Activating the bicep allows us to lift our arm at the elbow; releasing our tricep allows us to lower our arm. Consider the bicep the creative muscle, the tricep the judgmental muscle. What happens when a writer tries to use both muscles at once? Writers block.

Janet Emig—Her 1971 study "The Composing Processes of Twelfth Graders" was seminal in shifting focus to the writing process rather than just the final product.

Ann Haas Dyson—Dyson observed that children's writing development is deeply embedded in their social worlds. Children’s writing is influenced by peer interactions, popular culture, and community experiences; writing teachers do better when they invite writing under social circumstances instead of topical. Her research highlighted how children use multiple modes of expression (drawing, talk, play, and writing) to make meaning and communicate their ideas. Dyson's research has significant implications for curriculum design, suggesting the need for more flexible, socially-embedded approaches to teaching writing.

Linda Flower and John R. Hayes—Their cognitive process theory of writing, developed in the late 1970s and early 1980s, became highly influential in understanding how writers think.

Donald Graves—Graves conducted extensive research observing how children write, leading to his influential book "Writing: Teachers and Children at Work" (1983). An advocate for giving students more choice in their writing topics, he discussed the importance of teachers writing alongside students and of focusing on the process of writing rather than just the final product. Before Nancy Atwell and Lucy Calkins whose work ipromoted the idea of writing workshops in classrooms, Donald Graves wrote about classrooms where students could engage in regular, sustained writing practice. Graves also has important things to say about conferencing between teachers and students about their writing.

Ken Macrorie—Known for promoting authentic voice in student writing and his book "Telling Writing" (1970), Macrorie put a premium on authenticity, encouraging students to write in a way that tells their truth, expressing their genuine thoughts, feelings, and experiences. "Telling" writing is about conveying ideas clearly and directly, without embellishment, piled up adjectives, or academic jargon. The goal is to write in a way that communicates with the reader human to human, rather than fulfilling an assignment for a grade. Developing a personal, distinctive voice in writing rather than trying to imitate a formal academic style produces honest expression, being straightforward, avoiding empty phrases associated with assignments made with a required word length.

[Quick note: Nothing against word length assignments. Writers face routine constraints on space and have to deal with them. You only get so much canvas in many venues. A great assignment is to ask students to go back to a piece of prose they wrote a month ago and then cut its length by 20%. The grade is based on the level of detail included in a reflective memo detailing how and why they cut back. The same process works with common texts already published.]

James Moffett—His work on the development of discourse and student-centered curriculum had a significant impact on writing instruction.

Donald Murray—His work advocated for a process-oriented approach to teaching writing, influencing many educators with books like "A Writer Teaches Writing" (1968).

Mike Rose—His 1989 book "Lives on the Boundary" was highly influential, combining personal narrative with scholarly analysis to explore the challenges faced by underprepared students.

Mina Shaughnessy—Her 1977 book "Errors and Expectations" was groundbreaking in addressing the needs of basic writers in college. She took a cognitive approach and argued that many errors were not random but reflected students' logical attempts to apply rules they had learned, albeit incorrectly. Shaughnessy insisted that teachers not question the intelligence and potential of basic writers, challenging deficit models of education. The book addressed how teacher expectations could influence student performance and advocated for high standards coupled with supportive instruction. Shaughnessy offered practical strategies for teaching writing to underprepared students.

Keep in mind that writing teachers regardless of their grade level assignment need to know something about the arc of writing development across the years. Unlike reading competence, which develops more quickly and in recognized bursts of growth, writing competence develops more slowly, and teachers in a system must have a working knowledge of the endgame—college and career readiness and college itself.

**********

The terms ‘fair’ and ‘authentic’ from the pen of the National Commission index two crucial principles in public discourse from twenty years ago relevant to writing assessment that have been refined and redefined in today’s United States. Reliability and validity, time-honored characteristics of good assessments, seem to have reestablished themselves under the powerful shift from an “authentic” focus back to a more “standardized” measurement mindset ushered in with the Common Core. In the case of writing, construct validity and consistency of scores across assessment tools and/or judgments are highly significant under the current meaning of equity.

Authenticity as a concept has deep roots, but its use has thinned and in some ways weakened. Authentic assessments have always involved tasks that allegedly mirror real-world writing activities. Classroom assignments or curriculum-embedded performance tasks that have practical applications outside the classroom map loosely onto the notion of construct validity, but as near as I understand the situation, throughout the grade levels teachers are aware of and comfortable with the narrowing of writing pedagogy that privileges argumentation based on textual evidence, a sort of lawyerly writing as the pinnacle writing task, which ignores the principle of authenticity.

In the dawn of authentic assessment in the 1980s, the notion of ownership as a learning outcome superseded the importance of text-based outcomes from cookie-cutter class writing assignments, which pulled each writer’s strings like a collection of cognitive puppets. Ownership meant that student writers worked on texts that served their own negotiated purposes and minimized instructional control of or intrusion into writing activities.

With the advent of No Child Left Behind and the Common Core, writing instruction appears to have been pushed toward a more structured, teacher-centered model against the grain theories that value ownership above texts, perhaps one of the key obstacles to implementing portfolio writing assessment not just for classroom evaluation, but for schoolwide accreditation reviews and statewide accountability measures.

The advent of large language models (AI) capable of generating cookie-cutter essays of a higher performance quality than many students in middle and high school can write has created fear and trembling among many writing teachers. This angst speaks to the degree to which a standardized, rhetorical instructional method has eaten to the entire curriculum. The concept of ownership and intentionality as a writer as well as the original meaning of authenticity could reduce the long term threat that AI will destroy students’ capacity to write. Students with an authentic voice and perspective will value the affordances of AI to help them create even more effective texts.

Nurturing ownership in no way suggests that students should not get writing assignments. Good writers in the real world take up writing assignments and projects on behalf of an agency, an institution, a company, a political structure, a newspaper—the real world is a maze of possible assignments on and off the job. Writers need to learn how to scope out the parameters of assigned tasks and find a way to own them through experiences with assignments. Indeed, portfolio assessment involves ensuring that the assessment context closely represents the diverse and complex environments in which students will write outside the classroom, including assignments relating tasks to real-world scenarios and interdisciplinary contexts.

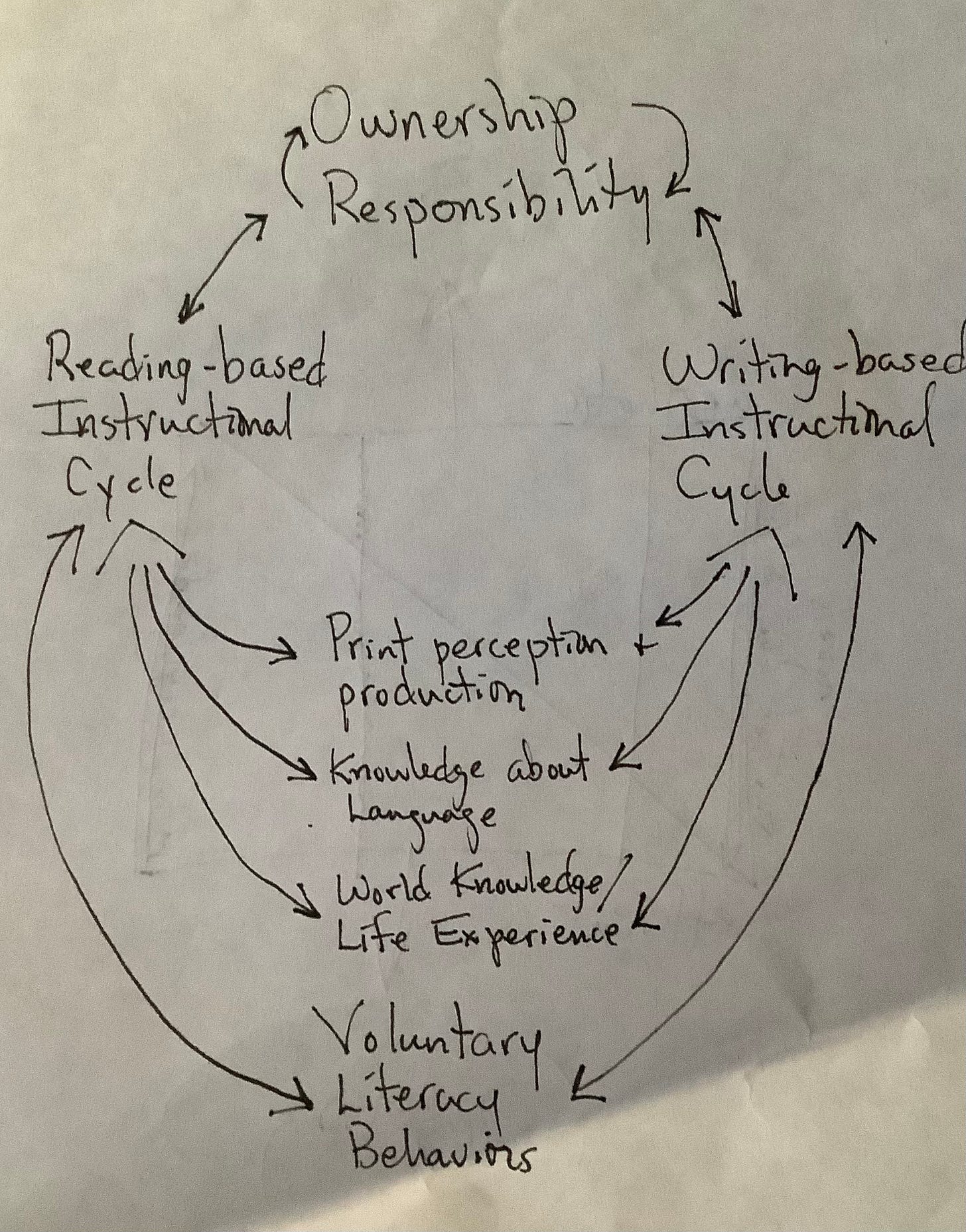

In the late 1980s I found myself doing presentations and workshops on portfolio assessment. My views had been heavily shaped by Donald Grave’s argument that schools did such a weak job of graduating strong writers as a result of the ubiquity of “Writers’ Welfare.” The following image of a diagram I created then presents my way of conceptualizing at the time the centrality of ownership in both reading and writing pedagogy:

When the Neglected R was published in 2003, it was one of those national omg moments, they (policy makers) have to listen now, similar to the call to do better in reading instruction when A Nation at Risk (1983) was circulating and disrupting the education bandwidth. The National Writing Project published a call to action just a year ago in 2023 essentially revoicing concerns raised in the Neglected R. The Commission (2003) and the National Writing Project (2023) concurred that substantial and meaningful change awaits changes in teacher preparation, including a course dedicated to writing instruction in every secondary teacher preparation program just as there exists a requirement for preparation to deliver disciplinary reading instruction. I would argue that portfolio assessment strategies ought to frame any course in writing instruction.

*****

The term "portfolio" had no situated, shared meaning in formal schooling before the 1980s when writing teachers began to question the ontological validity of product-based evaluation. In the 70s theorists were engaged in a prolonged, introspective exploration of writing as process, nothing like the assign-demand-and-grade paradigm. Janet Emig (1977) published a seminal piece in College Composition and Communication titled “Writing as a Mode of Learning,” proposing that “…writing uniquely corresponds to certain learning strategies” (p.122) and that “…the losses to learners of not writing are compelling…[and without instructional change] writing itself as a central academic process may not long endure” (p.129). Viewing writing assignments as opportunities to evaluate rather than opportunities to learn, believing that students will not write unless they are graded indeed can erode writing to learn—which, by the way, can be assessed vis a vis portfolios.

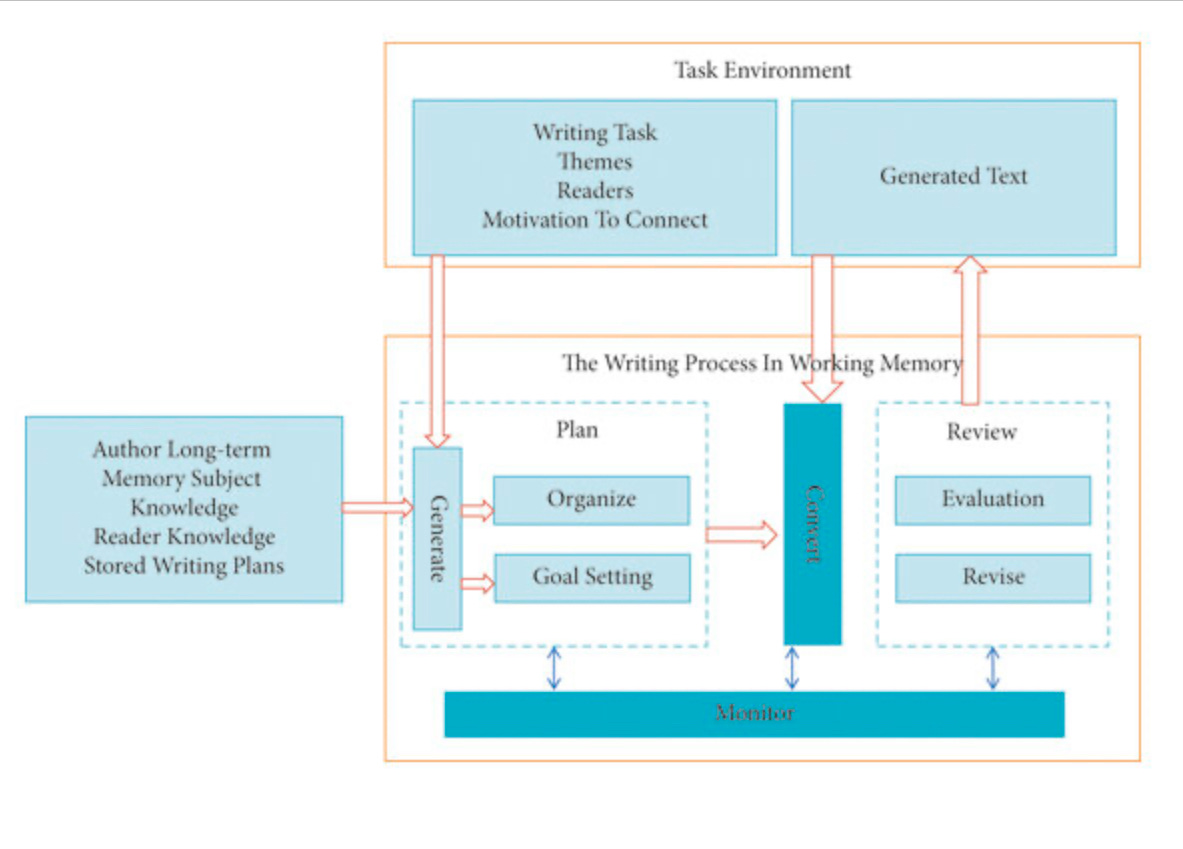

After cognitive psychologists got involved and sketched rectangular models with components, arrows, and feedback loops, an effort which amounted to laying bare what happens in the brain during these subprocesses step by step by step, the research compelled curriculum writers to produce assignment scripts or scenarios for delivery to classrooms for delivery to children.

I remember a school ordering six thick color-coded check-out-able binders with hundreds of pages, each holding six binders, one per grade level, complete scripted think-sheeted writing projects easily implemented with a ditto machine and a predetermined time allotment—a schoolwide curriculum for the entire year, add water, spices to taste, voila. Such curriculum materials represented a complete misunderstanding of this cognitive model. Witness Flower and Hayes (1981):

As these research strands merged over time, the more philosophical stance represented by Emig and the more scientific stance by Flower and Hayes, the notion of a “writing process”—THE writing process—entered the daily grind of instruction through osmosis. Because the diagram laid out the steps so clearly, lesson plans could be made quickly and easily. I’ve seen variations of Flower and Hayes in the frantic explorations of current educators looking for places in THE process where AI should be verboten or encouraged. While the impulse to guide uses of AI is legit, inserting cookie-cutter AI activities inside a cookie-cutter writing precise undermines ownership.

In fact, in Flower and Hayes’ discussion of their model in real-world scenarios, they discourage any attempt to map out the process and use it to “stage” assignments. A smooth ride from prewriting to drafting to revising to editing to polishing to submission for a grade distorts the meaning of their contribution. They found in their data that “writing is a goal-directed process…writers create a hierarchical network of goals and these in turn guide the writing process” (p.376). By modus ponens, writing instructors who dictate the goals of each step in the writing process and think-sheet their writers through a linear sequence deny them the opportunity to become goal-driven writers searching for innovative ways to create texts.

“Process goals are essentially the instructions people give themselves about how to carry out the writing process….Good writers often give themselves many such instructions and seem to have greater conscious control over their own process than the poorer writers we have studied” (p.376)

Over time researchers in writing moved beyond a purely cognitive focus on individual thinking during writing activities to look into the role of social and cultural factors in evoking new writing goals or modifications as writers networked within a community of writers. As noted above, Ann Haas Dyson at UC Berkeley documented the centrality of social worlds in the emergence of early writing. As near as I can tell, early writing instruction today is often filled with prescribed content and taken up as a way to teach phonological encoding and orthographic expertise.

Spears (1988) published a book titled Sharing Writing: Peer Response Groups in English Classrooms exploring “…the gap between theory and practice in the use of response groups [to provide] a detailed analysis of students’ problems in writing groups” (p.1) along with discussions of techniques and suggestions for teaching productive activity leading to enhanced awareness of text as cultural and communication artifacts. The teacher’s instructional role includes implementing strategies for teaching and assessing students to monitor their individually effective strategies for honing and defining an individual hierarchy of goals for completing a piece of writing and for harvesting useful feedback regarding those goals from peers.

Given a more complex view of writing processes as a combination of individual ownership, responsibility, and intentionality—the notion of authoring—in a community of peers involved in exploring their own capacity for authoring, portfolio assessment may be not just the best, but the only way for teachers to know how best to teach a particular community of writers.

My fourth grade students (1986-1989) taught me the central role of experimentation in learning—trying a new trick or tool sometimes produces a failed piece of writing but expands knowledge gained from experience, particularly if the learner set out to expand an emerging skill. Developing writers reaching toward elements beyond their mastery often seem to be moving backwards. The significant assessment question for a teacher is why. Working portfolios structured to give learners ways to document their writing decisions in the context of reflective analysis opened my eyes to the critical nature of understanding what the learner was trying to do as a basis for understanding what was actually done.

I believe with careful thought and planning, a portfolio strategy can place the responsibility on learners for providing their teacher with insights into their development. With a focus on growth rather than grades, in a setting where students are sharing vulnerabilities as writers, this approach can give teachers a path to discern how students find a pathway from AI plagiarism to AI affordances without formally charging them with plagiarism before they’ve had opportunities to learn how to use AI as a tool vis a vis their hierarchical set of goals established (not prescribed) during intitial forays into a writing project.

***

As a portfolio researcher during the 1990s, I was interested in precursors to the writing portfolio in history. During the Renaissance artists like Leonardo da Vinci kept notebooks and sketchbooks over a lifetime to keep their ideas fresh, to remind them of significant scientific and aesthetic discoveries which could have been lost and forgotten. I saw the seeds of a writer’s working portfolio in the Renaissance, a place to keep textual artifacts to anchor a work flow over long periods, to ensure valuable material would not be lost. These practices illuminate for me the idea of “portfolio thinking,” the awareness that what I’m working on right now can teach me now and in the future.

During the 18th and 19th centuries "portfolio" began to be used more transactionally. Painters and sculptors collected finished drawings and sketches to show potential patrons or to use as references for larger works. With the rise of photography, artists began to create more formal collections of their work for presentation. This period saw the portfolio concept becoming more structured and purposeful. The modern concept of an artist's portfolio as a curated collection of best works for professional presentation became well-established. Art schools began requiring portfolios for admission. Leonardo’s perspective might be viewed as a sort of process folio for learning. Enlightenment portfolios might be viewed as product folios, a helpful distinction.

Dennie Palmer Wolf, a researcher in art education and portfolio assessment who has published a rich body of work beginning in the 1980s, validated the core notions of portfolio pedagogy and assessment in a 1989 piece titled “Portfolio Assessment: Sampling Student Work.” Digging into her research over time uncovers a stunning array of insights into assessment. The following excerpt from the 1989 piece provides a flavor for what she has contributed to assessment theory:

***

In the financial sector in the 1950s, a portfolio meant a collection of investments held by an individual or organization. In 1952, Harry Markowitz published his thoughts on a Modern Portfolio Theory, which influenced how businesses and investors managed collections of assets.

“Harry Markowitz (born 1927) is a Nobel Prize-winning American economist best known for developing Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT), a groundbreaking investment strategy based on his realization that the performance of an individual stock is not as important as the performance and composition of an investor's entire portfolio” (Ann Behan, 2022).

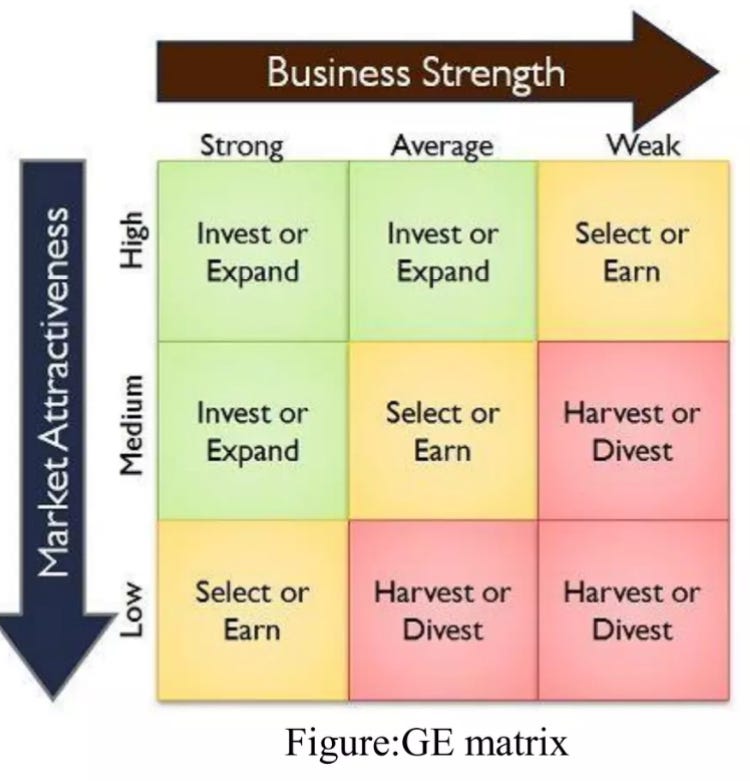

In the 1970s the concept of "portfolio management" gained traction in corporate strategy. Bruce Henderson of the Boston Consulting Group introduced the “BCG Growth-Share Matrix,” a tool to categorize a company's business units or products into four quadrants: Stars, Cash Cows, Question Marks, and Dogs based on market growth and relative market share.

“Products that are in low-growth areas but for which the company has a relatively large market share are considered cash cows. The company should milk the cash cow for as long as it can” (Adam Hayes, 2024).

In the early 1970s, General Electric, working with McKinsey & Company, developed a more complex nine-cell matrix for portfolio analysis, considering industry attractiveness and business unit strength, providing a more nuanced approach to portfolio management. This matrix is important in investment analysis still today.

Although the relevance of the financial portfolio to writing portfolios isn’t so obvious, with a bit of cogitation and prestidigitations parallels are visible. The business portfolio contains documents which hold value just as a writing portfolio contains documents. Here’s the difference: Value comes from the external world in the financial portfolio; the owner of the folio has little control over this value except to decide whether to hold or sell an asset.

If writing portfolios operated on this plan, students would play no part in valuing their work; instead, they would wait for the ticker tape from the teacher with a grade. Portfolio systems for writers slowly wean learners from depending on an authority figure to inform them of the value of their writing, undercutting any chance of their experimenting and reflecting on their self-proclaimed failures.

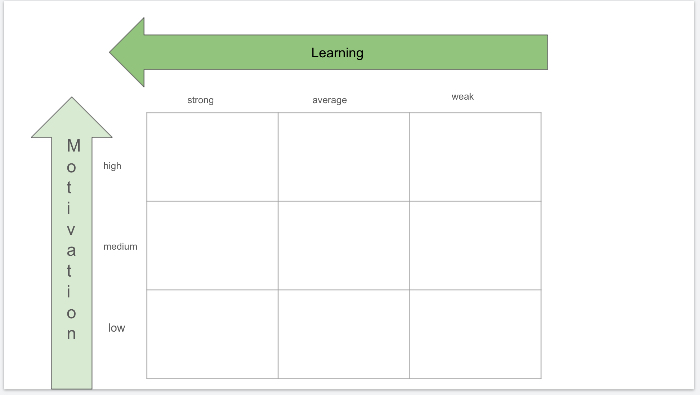

This nine-cell matrix, however, provides a heuristic useful to teachers in making private judgments about student growth without the daily dose of points or credits or checkmarks or grades. Here is a version of this matrix I created to stimulate discussion:

The arrows represent core outcomes teachers seek to impact through their work. Learning is another gerund like “writing,” a usage that can be read as a noun or a verb. As a noun, learning is frozen in time, an object, measured by one or another instrument to produce a number or a letter grade as a proxy. As a verb, learning is actions and insights gained from those actions. In this sense, learning is a cycle begun with a set of goals and an intention, a deliberate plan of action with situated specifics, a momentum that deepens and broadens expertise, and reflective analysis of artifacts and products to glean insights, refine expertise, and set new goals.

Motivation isn’t usually graded. Teachers often believe they aren’t teaching motivation, that the drive to learn is inherently learner territory beyond their reach. Many teachers have told me that grades are their chief motivator. In a classroom community that values and asks students for evidence to demonstrate their level of motivation, however, I can testify, based on my dissertation research, that most students reorient themselves and come to understand that consistent, hard work is rewarding for itself. Choice is a crucial element in this sort of pedagogy.

They also come to see that hard work is related to learning and improvement, part of the explanation for their growing expertise. Learning also isn’t usually graded. Instead, knowledge or production or right answers or following directions are formally valued. In a portfolio culture students learn not only that they are responsible for their own learning, but that they can shape it and direct it and that their growing expertise is their own. In m view, this theory of learning can accommodate pedagogy in courses ranging from writing poetry to expertise in anatomy and physiology. Back in the day I read a study of a portfolio system designed to improve both learning and certification of cadets in a 26-week course leading to employment as a police officer.

This is the theory anyway, and the theory was gaining ground in practice when the idea of portfolios and its intersection with how writers learn was relegated to the back burner once schools were mandated to improve standardized tests scores year after year, the effect of NCLB. The narrowing Common Core effect of argumentation as the ultimate achievement of college and career readiness also made moot the issue of teaching writing for depth and breadth of genre expertise.

The most disturbing aspect, personally, is the portfolio amnesia I see. Beginning with the adding of e- to the word portfolio, the dominant view of portfolios seems to be as a collection of graded assignments. The required parts of the folio, the focus on accountability for learning rather than its ownership, rendered the prevailing concept a reversed image of the notion I studied for my dissertation. The promises of portfolios remain unfulfilled.

*****

In an effort to reignite interest among teachers in portfolio pedagogy and assessment, especially important in an AI world, I wrote this post for Nick’s collaborative. I plan to contribute another post soon focused on the thorny issue of grading. I’ve had experiences writing portfolio manuals that students use to help them navigate local designs and will offer support and feedback for system designers who contact Nick and work in conjunction with his collaborative.

Everyone wants to know what portfolio assessment is. I see the concept as a cultural rather than a technical matter. I came to call the portfolio a chameleon back in the day, a local creature that blends into the surround. Murphy and Underwood (2000) in their book Portfolio Practices: Lessons from Schools, Districts, and States published by Christopher Gordon, write the following in their concluding chapter to reinforce the idea that portfolios are not cookie cutters of various sizes, small ones for schools, bigger ones for districts, huge one for states:

“From our perspective, a striking lesson from all of these histories—perhaps the distinguishing feature that makes portfolios what they are—is the fact that portfolio assessments are inseparable from the people and situations in which they were made and used…. Like Frank Lloyd Wright’s buildings, the portfolio systems profiled here were not prefabricated. Instead, they were intertwined with and shaped by the social, ideological, cultural, and institutional aspects of the institutions in which they emerged” (Murphy and Underwood, 2000, p.281).

Check out some of my favorite Substacks:

Terry Underwood’s Learning to Read, Reading to Learn: The most penetrating investigation of the intersections between compositional theory, literacy studies, and AI on the internet!!!

Suzi’s When Life Gives You AI: An cutting-edge exploration of the intersection among computer science, neuroscience, and philosophy

Alejandro Piad Morffis’s Mostly Harmless Ideas: Unmatched investigations into coding, machine learning, computational theory, and practical AI applications

Michael Woudenberg’s Polymathic Being: Polymathic wisdom brought to you every Sunday morning with your first cup of coffee

Rob Nelson’s AI Log: Incredibly deep and insightful essay about AI’s impact on higher ed, society, and culture.

Michael Spencer’s AI Supremacy: The most comprehensive and current analysis of AI news and trends, featuring numerous intriguing guest posts

Daniel Bashir’s The Gradient Podcast: The top interviews with leading AI experts, researchers, developers, and linguists.

Daniel Nest’s Why Try AI?: The most amazing updates on AI tools and techniques

Riccardo Vocca’s The Intelligent Friend: An intriguing examination of the diverse ways AI is transforming our lives and the world around us.

Jason Gulya’s The AI Edventure: An important exploration of cutting edge innovations in AI-responsive curriculum and pedagogy.

This post is tremendously helpful in laying out what’s gone wrong with writing instruction since the early 2000s and why a return to focusing on the individual intention, responsibility, and authenticity of a student writer’s work - their growth and learning over time - matters so much when it comes to incorporating generative AI in the classroom. Terry, thank you for bringing together your wealth of knowledge here (I’ll have more to say on your site). Nick, thanks for publishing this educational venue on AI, which I’m very happy to have found - a humanist approach to how AI can tap social and cultural aspects of authorship really speaks to my own writing now about AI and the threat (or hope) it poses for self-expression.

Thanks for this. I'm excited for the follow up!