Process Tracking Is Not the Answer

Why Trust, Not Surveillance, Must Guide Us in the Age of AI

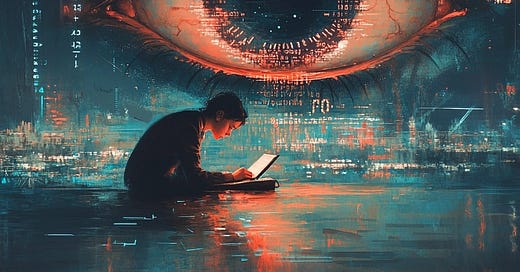

In the ongoing scramble to respond to generative AI in education, the latest shiny solution now entering the scene is "process tracking"—a technique that monitors how a student writes, logging every keystroke, pause, paste, and revision. At first glance, it might seem like an elegant response to the growing challenge of AI-assisted academic dishonesty. After all, if you can see the writing process itself, surely you can tell if it's genuine. But if the last few years have taught us anything, it’s that chasing technological certainty through surveillance leads us deeper into a pedagogical cul-de-sac. Process tracking, like its predecessors, serves institutional anxieties more than it supports student learning.

If this work resonates with you, consider becoming a paid subscriber to support independent research grounded in critical analysis and pragmatic insight.

What Process Tracking Actually Does—and the Epistemology It Assumes

Tools like Grammarly's Authorship and Turnitin's new Clarity platform promise a data-driven window into the student's writing process. These systems generate temporal and behavioral metadata: timestamps of when text was written, how it was inserted (typed, pasted, generated), and how much time was spent in each revision cycle. On the surface, this seems useful—who wouldn't want to distinguish a carefully developed essay from a copy-pasted AI draft?

But these tools do more than observe—they interpret. They reframe composition as a behavior to be audited, rendering the cognitive and affective work of writing legible only through quantifiable proxies. This shift is epistemological. It substitutes observable behavior for learning. As scholars like Gert Biesta have argued, education is not reducible to outcomes or observable performances; it is about subjectification—the process of becoming someone who engages the world meaningfully. Process tracking, by contrast, makes students legible to institutions as risk profiles.

Anna Mills and the Pedagogy of Empirical Pragmatism

enters this conversation not as a technophile or a traditionalist, but as an empiricist—committed to close observation, practical outcomes, and grounded interventions. Her work reflects a careful, good-faith inquiry into what students need, how teachers can respond, and where tools might genuinely support integrity. Her engagement with Grammarly Authorship is framed by a desire to give students agency in demonstrating the provenance of their writing.This position, rooted in a pedagogy of transparency, deserves careful consideration. Mills distinguishes between coercive surveillance and consensual accountability. Her emphasis on student-controlled reports and opt-in participation reflects a broader belief in mutual trust. That said, her perspective might not sit easily with more critical framings of surveillance. While her approach mitigates some harms, it may also risk normalizing the infrastructure that enables them.

This tension matters. Her work poses a necessary question: If process tracking is already here, how do we use it in the least harmful way? But the broader argument of this essay is that such a concession—even when made in good faith—risks legitimizing a fundamentally flawed premise: that student integrity can and should be validated through digital trace data.

Have We Learned Nothing from the First Wave?

The first generation of AI detectors—those that analyzed text for telltale signs of machine authorship—have largely failed. They misclassified human writing as AI-generated, disproportionately flagged work by multilingual and neurodivergent students, and operated as black boxes with little pedagogical value. These failures were not simply technical—they were ideological. As Cathy O’Neil warns in Weapons of Math Destruction, when opaque models govern high-stakes decisions, they reproduce bias and entrench inequality.

Process tracking risks inheriting the same logic: replacing pedagogical judgment with algorithmic inference. It extends the reach of what Michel Foucault called the "panoptic gaze"—a mode of power that disciplines not through punishment but through internalized surveillance. A student who knows they are being tracked does not need to be punished to be controlled. The mere awareness of visibility reshapes their behavior. And what is lost, often irretrievably, is the freedom to write badly, weirdly, honestly.

What Kind of Writing Are We Protecting?

To what end is all this scrutiny directed? If the goal is to preserve academic integrity, we must interrogate what we mean by that phrase. Too often, integrity is conflated with conformity—fidelity to outdated norms of authorship and individual production. But composition scholars have long challenged the myth of the isolated writer. Writing is intertextual, social, scaffolded. AI complicates authorship, but it does not destroy it. As scholars like Kathleen Blake Yancey and Rebecca Moore Howard have shown, the boundaries of plagiarism and originality were already porous.

Instead of asking whether a student wrote "every word," we should be asking whether they engaged with the task meaningfully, whether they developed an argument, whether they took intellectual risks. These are not questions that metadata can answer. They require conversation, reflection, and the kind of teacher-student relationship that process tracking, paradoxically, may erode.

The Labor Politics of Detection

We must also consider who is doing the labor of detection, and who benefits. For overburdened adjuncts and under-resourced faculty, the promise of a dashboard that flags anomalies may be tempting. But this labor-saving illusion comes at a cost. It transforms instructors from mentors into monitors. It shifts assessment from human judgment to automated suspicion. And it feeds a growing industry of edtech firms that profit not from learning, but from fear.

Meanwhile, students—especially those already on the margins—absorb the consequences. They navigate a pedagogical minefield where one misstep in the writing process, one copy-paste for convenience, one draft written offline, can become grounds for disciplinary action. The message is clear: you are not to be trusted unless you prove yourself innocent.

Toward a Post-Surveillance Pedagogy

What might it mean to reject the premise of process tracking altogether—not to be naïve, but to be brave? A post-surveillance pedagogy does not mean abandoning standards; it means reimagining them in light of new realities. This would begin by shifting from forensic accountability to formative engagement.

Concretely, a post-surveillance classroom might include:

AI process narratives, where students reflect on how, when, and why they used generative tools in an assignment.

Collaborative authorship models, acknowledging that writing is often dialogic, peer-informed, and scaffolded.

Multimodal and recursive assessments, including drafts, voice memos, planning documents, and annotations as evidence of learning.

Pedagogies of mutuality, where instructors share their own processes and choices around AI use.

Institutional protections for academic freedom, preventing surveillance-based policies from being imposed unilaterally.

We might also reframe our learning goals: not “Did the student write this unaided?” but “What did the student learn in the act of composing—and how might we see and support that learning more fully?” This approach would require time, dialogue, and trust—resources often in short supply, but foundational to any transformative pedagogy.

We might also consider frameworks like Jesse Stommel’s pedagogy of care, which centers student agency, transparency, and mutual trust. Or the call from Ruha Benjamin to consider not only what tools do but what they undo—how they reconfigure relationships, values, and power.

As

writes, "The path forward isn't more sophisticated tracking of keystrokes, but more purposeful and meaningful engagement with students about why and how they write." This is not a sentimentalism—it is a wager on pedagogy itself.Conclusion: Refusing the Logic of Suspicion

Let’s not build a future of education on a foundation of mistrust. Let’s refuse the logic that sees students as problems to be solved algorithmically. Let’s imagine a classroom where integrity is cultivated, not surveilled; where writing is messy, human, and irreducible to metadata.

If AI is here to stay—and it is—then our job is not to police its borders, but to teach within its terrain. And that begins, always, with trust.

Nick Potkalitsky, Ph.D.

Check out some of our favorite Substacks:

Mike Kentz’s AI EduPathways: Insights from one of our most insightful, creative, and eloquent AI educators in the business!!!

Terry Underwood’s Learning to Read, Reading to Learn: The most penetrating investigation of the intersections between compositional theory, literacy studies, and AI on the internet!!!

Suzi’s When Life Gives You AI: An cutting-edge exploration of the intersection among computer science, neuroscience, and philosophy

Alejandro Piad Morffis’s The Computerist Journal: Unmatched investigations into coding, machine learning, computational theory, and practical AI applications

Michael Woudenberg’s Polymathic Being: Polymathic wisdom brought to you every Sunday morning with your first cup of coffee

Rob Nelson’s AI Log: Incredibly deep and insightful essay about AI’s impact on higher ed, society, and culture.

Michael Spencer’s AI Supremacy: The most comprehensive and current analysis of AI news and trends, featuring numerous intriguing guest posts

Daniel Bashir’s The Gradient Podcast: The top interviews with leading AI experts, researchers, developers, and linguists.

Daniel Nest’s Why Try AI?: The most amazing updates on AI tools and techniques

Riccardo Vocca’s The Intelligent Friend: An intriguing examination of the diverse ways AI is transforming our lives and the world around us.

Jason Gulya’s The AI Edventure: An important exploration of cutting edge innovations in AI-responsive curriculum and pedagogy.

Yes, multimodality gets tricky with assessments. Ideally, you would set core standards or outcomes achievable through both modes. Not always easy to accomplish. Good on you for trying!!!

Excellent as ever: thank you so much.

A way forward has to be multimodality & possibly choice of output. This works more in the year groups which don’t have essay-based, high stakes exams to prep for. If the assessments moved away from essays and writing - in my subject at least, English - as the ONLY acceptable form of assessment then teachers and students alike would be freed up from the need to examine full essay provenance. Plus, of course, they can get an answer from AI on one screen then type it out. Long winded but kids are nothing if not inventive in circumnavigating systems when they have left it to the last minute!

I set my yr 9s (13 yr olds) a choice of output for a short written homework recently.

Without AI - so handwritten or typed with a reflection, or, with AI + process disclosure (ie they handed in at least 2 versions, plus their prompts, plus a reflection, plus a load of other ‘processy’ things)

Most chose to just write the thing, unsurprisingly, as I’d made the “with AI” a bit of a faff, kind of deliberately to be honest.

Then, my marking became weird.

I realised that for one lot I was evaluating their creation and the other lot their process. I need to think about this a bit more carefully… all suggestions welcome!