Quantify or Qualify? The Future of Assessment in the Age of AI

Rethinking Assessment: AI's Role in a Process-Oriented Educational Landscape

Source: Midjourney, “The Clash Between the Quantifiable and the Ineffable”

Greetings, Amazing Readers of the Educating AI Substack!!!

I just finished up coordinating and leading my first AI x Education conference yesterday: “AI Essentials for Educators.”

We had great attendance and worked through 4 activity-filled sessions focused on (1) AI model selection and safety and security (2) writing and working with AI, (3) AI-responsive classroom pedagogies, and (4) AI-responsive school policies. I want to thank Blair Munhoven, Ed.D, for leading Session 4, and I want to express my gratitude to Bryan Lakatos for helping me workshop the ideas in Sessions 1 and 2. Check out my podcast with Bryan where we discussed some of the broader ramifications of AI integration late last summer.

One conference attendee, Marty Frasier, who gave me permission to use his response, commented:

As an English teacher and Dean of Faculty, I have been trying to figure out how to approach AI in my own classroom and also as a professional development tool. This conference allowed me to think about how to navigate AI at a variety of levels--from the most on-the-ground level in classroom settings to higher level policy and ethical considerations across educational institutions. I appreciated the range of opportunities to dig into complex questions and left with concrete next steps as well as sustained inspiration to keep tackling this new frontier.

Thanks, Marty!!! I too found the day immensely inspiring. Given the complexities and opportunities AI presents in education, collaboration and training are more vital than ever. Send me a direct message or connect with me on Linkedin if you are interested in setting up a similar training at your school in the summer or early next school year. Our participants found the material challenging, yet our surveys indicate that they left the experience feeling more confident about using and implementing AI in both their professional roles and daily lives, thanks to the training provided.

Before I begin today’s article proper, I want to thank my readers who have decided to support my Substack via paid subscriptions. I appreciate this vote of confidence. Your contributions allow me to dedicate more time to research, writing, and building Educating AI's network of contributors, resources, and materials.

Introduction: Process vs. Product in Education

Today, we continue our exploration of process-oriented education in the transformative era of AI. In this edition, we delve into the historical evolution of product-oriented education, and use this examination as a launch pad for the redefinition the contemporary classroom as a crucible for reimagination and renewal.

As all educational environments are intricately woven into complex systems of power, no educator can completely detach their teaching spaces from the prevailing product-oriented expectations. However, it is essential to acknowledge the significant influence educators hold in this transitional moment. This influence is crucial as we navigate how, amidst evolving classroom dynamics, AI can become a pivotal ally in fostering rich process-oriented pedagogies, transforming traditional educational models into vibrant arenas of innovative learning.

As I prepared this article, I found inspiration in a post by

: “The Chilling Truth About Teachers: Ed3 World Newsletter Issue #30.” Despite the ominous nature of the title, Vriti’s message carries a deep sense of hope for both teachers and students. She argues that the 3rd AI Age presents a unique opportunity for transformative change in education. By reevaluating and realigning our institutional and instructional values, we can make schools more welcoming, joyful, and sustainable places.Part One: The Historical Trajectory of Product-Oriented Education

The inception of product-oriented education is deeply rooted in the Industrial Revolution, an era characterized by a burgeoning demand for standardization and uniformity across all sectors, including human labor. Educational systems of the time responded aptly to this industrial call, mirroring factory-like precision in their regimented structures, punctuality, and a pronounced emphasis on repetitive tasks—all meticulously designed to cultivate a predictable and uniform workforce.

As the 19th century dawned, this ethos found robust expression in the Prussian education system, which became a paradigm of structured schooling. The Prussian model introduced a hierarchy that was rigidly adhered to, along with a standardized curriculum that was state-directed, aiming to mold students into well-disciplined products ready for governmental and industrial needs. This system profoundly influenced educational practices not only in Germany but across the world, particularly in the United States.

Grading Systems Across Institutions:

Yale University’s Early Grading Practices: Yale was a pioneer in formal grading systems, instituting a scheme as early as the late 18th century where students were categorized into four ranks based on their academic performance: "Optimi" (the best), "Second Optimi," "Inferiores" (lower), and "Pejores" (worst). This early attempt at structured grading underscored the competitive academic environment of the time.

University of Cambridge’s Tripos System: Cambridge’s Tripos system is another early example of academic ranking, introduced in the 19th century. It was famously demanding, culminating in the "order of merit," which publicly ranked students based on their examination performances. This not only promoted a fiercely competitive academic culture but also reinforced a meritocratic ethos within the educational system.

The French Lycée System: In France, following the revolutionary changes, the Napoleonic reforms established the Lycée system which formalized secondary education with a centralized approach. The grading in Lycées involved numeric scores and annual examinations that determined students’ progression and success, emphasizing a uniform standard across all state-run schools.

Prussian Educational Reforms: The Prussian system, often seen as the archetype of modern education systems, employed rigorous methods of student assessment. The curriculum was tightly controlled by the state, and student performance was systematically recorded and graded, reinforcing the factory model of education where students were treated as outputs of a well-oiled machine.

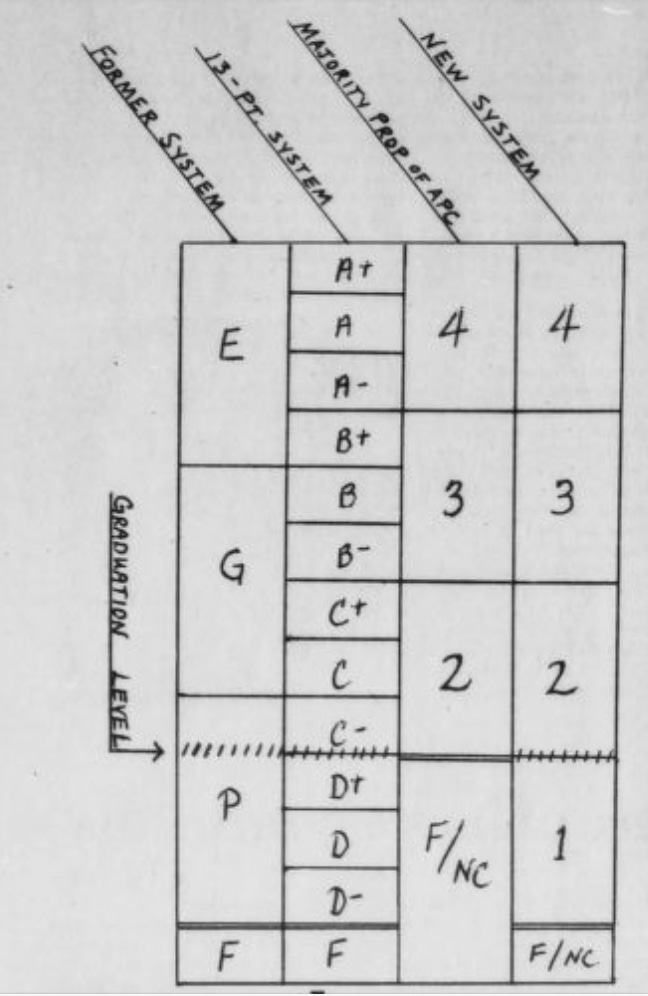

Mount Holyoke College’s Grading Innovations: In the United States, Mount Holyoke College introduced a more refined letter grading system in 1897, using grades A through E, where E typically indicated failure. This system marked a significant shift towards more granular assessments of student performance, setting a precedent for future educational assessments.

Source: “Know Our History: Grading at MHC”

These grading systems, though varied in their methods and historical contexts, all shared a common objective: to quantitatively assess and categorize student performance. This drive towards measurable educational outcomes is a testament to the lasting influence of the industrial model on education, reflecting a persistent legacy that continues to shape modern and contemporary educational practices.

Part Two: Evolution of Educational Assessment from the Early 20th Century to the Present

As we progress through this short history of educational assessment, the early-to-mid 20th century marks a pivotal era where psychological theories began to intersect more significantly with pedagogical practices. This period witnessed the rise of scientific behaviorism, the advent of standardized testing, and the integration of big data in educational strategies, each reflecting deeper societal shifts toward quantification and efficiency.

Behaviorism and Its Proponents:

Edward L. Thorndike's Connectionism: Thorndike introduced the theory of connectionism in the early 1900s (obliquely related to AI connectionism dating to the 1940s) positing that learning is the result of connections formed between stimuli and responses. His approach advocated for the measurable aspects of education, emphasizing reinforcement and the quantification of learning outcomes.

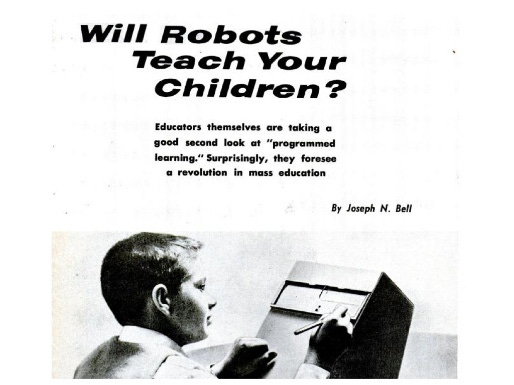

B.F. Skinner’s Operant Conditioning: Advancing further into behaviorism, Skinner's mid-20th-century work on operant conditioning applied these principles directly to education. His teaching machines and programmed instruction were innovations designed to reinforce learning through immediate feedback, pioneering early forms of what would evolve into computer-assisted learning. I plan on writing another article on Skinner’s teaching machines in the near future.

Source: HackEducation, “Teaching Machines Teaching at Scale”

Standardized Testing and Its Expansion:

Introduction of IQ Tests: The early 20th century saw the introduction of IQ tests by psychologists such as Alfred Binet, initially intended to identify students needing additional educational support. However, these tests quickly became tools for streaming students into different educational tracks, laying the groundwork for later standardized tests.

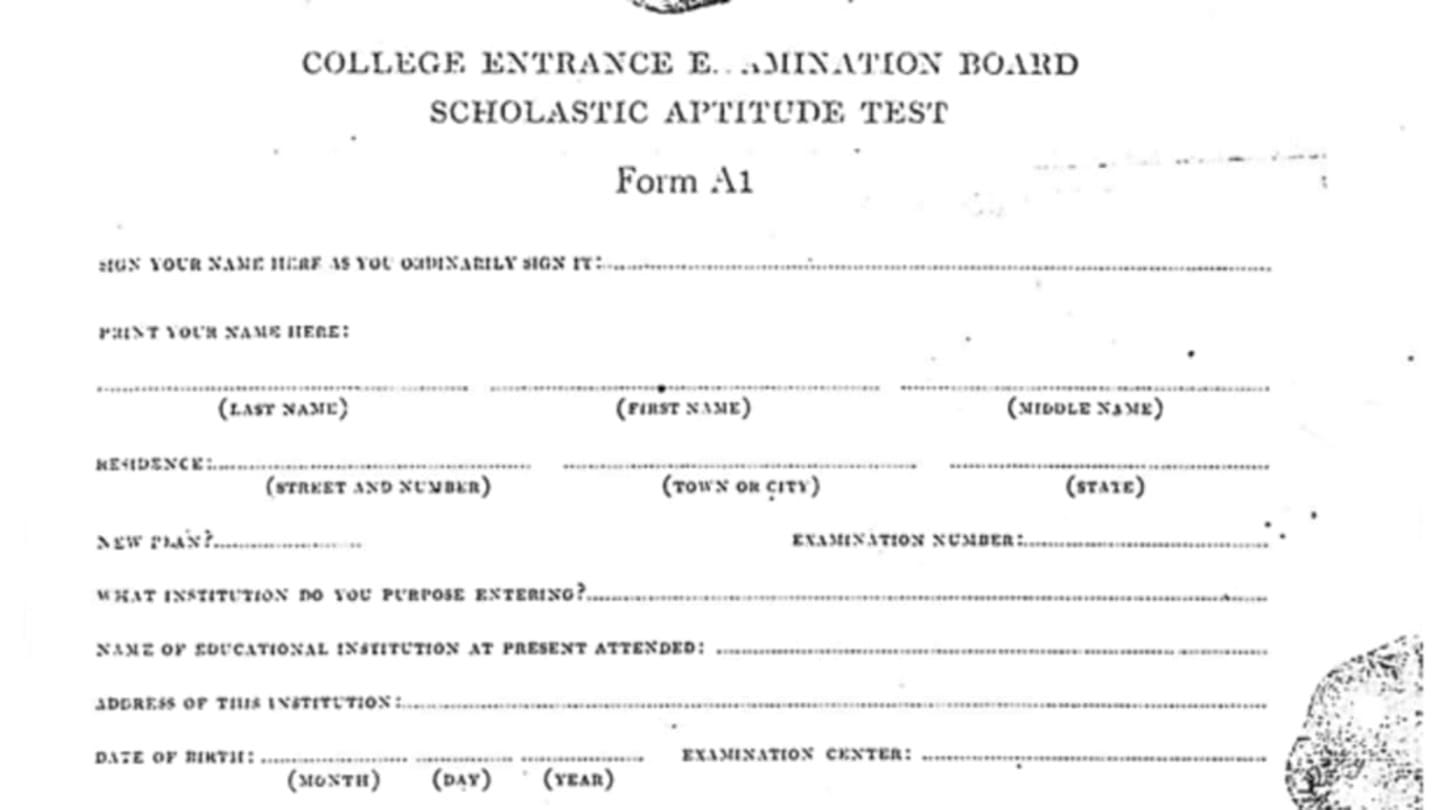

College Admission Tests: Standardized testing gained significant traction in the mid-20th century with the establishment of college admission tests like the SAT. These tests were designed to evaluate academic readiness for college, influencing admissions processes across the United States and reinforcing the meritocratic structure of higher education.

No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB): Enacted in 2001, NCLB mandated regular standardized testing in American schools to measure student performance, aiming to close educational gaps. This policy intensified the focus on quantifiable educational outcomes, linking funding and evaluations to test results, thereby concretizing the role of standardized assessments in educational accountability.

The Big Data Revolution in Education:

Data-Driven Instruction: The late 20th and early 21st centuries have seen a surge in data-driven educational practices, where student performance data is analyzed extensively to guide teaching methods, curricular adjustments, and educational policies. This approach emphasizes a granular analysis of learning processes, aiming to tailor educational experiences to individual student needs through adaptive learning technologies.

Impact of AI and Learning Analytics: The integration of AI and learning analytics in recent years has transformed educational assessment by enabling more sophisticated analyses of big data. This technological evolution supports a more personalized learning experience, though it also raises questions about privacy, data security, and the potential for reinforcing existing disparities.

Part Three: The Process-Oriented Classroom as a Space of Reinvention

The historical trajectory of education overwhelmingly tilts towards measurement, quantification, and product-orientation. This transformation has brought significant advancements in how we educate our students and children. By adopting the principles of systematicity, iterability, testability, quantifiability, and revisability from the scientific disciplines, education has reshaped itself from a mere adjunct to philosophy and rhetoric into a streamlined, maneuverable discipline capable of assessing and anticipating the impacts of nuanced changes within both local and broader educational contexts.

Yet, this shift has not come without sacrifices. We have relinquished something vital—education as a process. In our pursuit to control every aspect of educational environments to maximize outcomes and efficiency, we have obscured the inherently processual nature of ourselves, the spaces we occupy, and crucially, our students. Over the past four decades, technological innovations such as calculators, word processors, laptops, the internet, and cell phones have each sparked a reevaluation of the product-based orientation prevalent in contemporary education. However, none of these tools had the purposive algorithmic design and agentic potential that AI systems possess. With AI becoming increasingly sophisticated and capable of producing many of the outputs we demand from our students, it is imperative that we seriously consider recalibrating our focus. This is not just to avert a potential crisis in assessment and integrity but to craft a system that is more equitable, engaging, and ultimately, more effective.

Process as the Ineffable Foundation of Contemporary Educational Practice

As a related aside, it's fascinating to observe how educators are grappling with the construct of quantifiability at the very moment when computer scientists are endeavoring to mathematicize language—a pursuit that has yielded tangible results in the development of Large Language Models (LLMs). Despite the actionable success of these models, even the most empirically-oriented researchers and developers maintain a healthy skepticism towards reinvigorating Chomskyan ideas of a universal grammar.

They question assumptions that LLMs could ever achieve flawless mastery over the complexities of human language. A notable critic in this dialogue is Daniel Bashir from The Gradient podcast. Bashir challenges the leap some theorists make from practical applications to the notion of perfect, computable comprehension. He intriguingly continues to discuss concepts like “the ineffability of language,” engaging with the ongoing debate about how LLMs parse and predict human communicative patterns.

Here, I propose considering the concept of process as the "ineffable" in education. If history—from Kant through Einstein to Heisenberg and Quantum Mechanics—has shown us anything, it is that our efforts to quantify outcomes are invariably entangled with those outcomes themselves. Despite our best intentions to forge authentic, equitable, and objective measures, we, as processual beings, infuse every measurement with our presence. Consequently, our quantifications often reflect not a pristine potentiality or actuality but rather the imprint of our involvement, which contradicts the demands of our product-oriented systems.

Outlining the Imprint of the Ineffable through a Practice of Inquiry

Thus, the challenge is not to completely forsake measurement but to seek a system that better aligns with the real processes—including the rise and advancement of AI systems—we and our students engage in daily throughout the academic year.

What would it mean to develop process-oriented outcomes and to assess our students based on these criteria? How would this approach resonate with students? Could such a shift alter the dynamics of how students use AI tools, encouraging them to utilize AI for substantive utility over mere efficiency? Or would the prevailing product-driven cultural and institutional logics—rooted in meritocracy, capitalism, and the college admissions process—continue to undermine these more localized efforts?

Creating a Process-Oriented AI-Responsive Classroom Practice

Over the past several weeks, I have begun the gradual shift in my classroom from a focus on products to a focus on processes. Here are the steps I've implemented:

Empowering Student Agency: I've handed over nearly complete control of the writing process to my students, freeing them from prescribed outlines, assigned topics, and restrictions that previously stifled their creativity.

Dedicated Project Time: Approximately 80% of class time is now devoted to working on their writing projects, providing substantial space for development and exploration.

Personalized Instruction: I've transitioned to a one-on-one conference model, where students meet with me weekly to discuss their writing projects. This allows for personalized guidance and feedback.

Process-Focused Assessment: My evaluation criteria have shifted to concentrate on the writing process itself, rather than just the final product.

Revision Opportunities: Students can revise their work throughout the semester, encouraging continuous improvement and learning.

Reflective Writing Choices: While I no longer mandate that students write in either the first or third person, they are required to reflect on the impact of these choices in their process work.

Flexible AI Integration: Throughout the year, I've carefully fostered an environment where AI tool usage is optional. Currently, most students opt to use AI primarily for brainstorming, researching, rephrasing, and editing.

These changes aim to cultivate a classroom that values growth and learning in the writing process, reflecting a more dynamic and student-centered approach.

Let me know if any of these ideas or initiatives resonate with you. This summer, I'm considering expanding the scope of my Substack to more broadly address cultivating a meaningful, restorative, process-oriented life in an AI-driven world geared toward efficiency. While my primary focus as an educator will continue to be on AI integration and implementation, this expanded platform would enhance my impact not only professionally as a teacher and trainer but also personally as a husband, father, friend, and lifelong learner.

Thank you for being a part of this journey, dear readers!

Nick Potkalitsky, Ph.D.

Check out some of my favorite Substacks:

Terry Underwood’s Learning to Read, Reading to Learn: The most penetrating investigation of the intersection between compositional theory, literacy studies, and AI on the internet!!!

Suzi’s When Life Gives You AI: An cutting-edge exploration of the intersection among computer science, neuroscience, and philosophy

Alejandro Piad Morffis’s Mostly Harmless Ideas: Unmatched investigations into coding, machine learning, computational theory, and practical AI applications

Michael Woudenberg’s Polymathic Being: Polymathic wisdom brought to you every Sunday morning with your first cup of coffee

Nat’s The AI Observer: A fascinating investigation into the emergence of higher-order reasoning in advanced AI systems, complemented by amazing coding experiments

Michael Spencer’s AI Supremacy: The most comprehensive and current analysis of AI news and trends, featuring numerous intriguing guest posts

Daniel Bashir’s The Gradient Podcast: The top interviews with leading AI experts, researchers, developers, and linguists.

Daniel Nest’s Why Try AI?: The most amazing updates on AI tools and techniques

Riccardo Vocca’s The Intelligent Friend: An intriguing examination of the diverse ways AI is transforming our lives and the world around us

Love your writing and thinking Nick, and not sure how it’s progressed but for me a key question which you refer to is “What’s education for?” Think there’s a need for a deeper philosophical discussion now more than ever, and it links to my current mental struggle (in a good way and lots to talk about in relation to that but that’s for another time!) in making sense of what are essential/durable skills we need to all be fostering but particularly young people.

Yes. As far as I know, teachers have wide latitude to define their “grading” system. I know exactly what I would do—I could write a book about it (I have—two of them:)—but you need to learn it from your students. I would start off with a discussion: Ask them to debate the question “Grades good for learners? Yes or no. Let them talk in pairs, write in a journal if they want, talk it over with a bot first). Invite them to ask the bot for some thoughts on 1) why adults want schools to issue report cards and 2) how do universities use these reported grades? This leads naturally to a discussion of do I find grades valuable? Would I be more comfortable without them? Would I work harder? Deeper? Do I need my teacher to give me a grade with some stakes attached (GPA)? Keeping in mind I have to grade you or I’ll lose my job, let’s negotiate. Here are the parameters: Everyone reads books. Everyone writes. I reserve the right to assign readings sometimes, though never writings though you will have due dates for deliverables which I will assess based on how hard you worked and your reflections on what you learned. Let’s negotiate a working relationship here which lets me do what they pay me to do, that is,to have the privilege and the honor to teach you. (Please quote me if you use or paraphrase this language. I plan to cut and paste it into a post. I’m talking feedback, Nick. I just gave you some damned good feedback. I expect you to write some naturalistic posts with a strong focus on the learners—narrate and quote—so others can learned from you. My mentor, David Pearson, said to me upon the occasion of my inadequacy of thanking him for his teaching me during my dissertation, “Terry, here’s how you can repay me. Pay it forward. Treat your students like you think I treated you. It was a pleasure.”