The Critical Thinking Imperative: Thriving in an AI-Assisted Writing Landscape

A Guest Post with Alan Knowles on Rhetorical Load Sharing and AI Collaborative Writing

Reading time: 17 minutes

What you will learn:

How Rhetorical Load Sharing (RLS) and AI Collaborative Writing (AICW) are redefining the integration of AI in writing

Strategies for adapting writing pedagogy to cultivate critical skills in an AI-augmented environment

The future of professional writing and the importance of treating writing as data in the age of AI

Key considerations for ensuring equitable access to AI writing tools and balancing AI use with skill development in grades 7-12

If you're short on time, jump to the interview with Alan Knowles for incredibly insightful, thought-provoking content.

Also, don't miss the key takeaways section at the end, which summarizes the most crucial points and actionable advice from this groundbreaking discussion on AI-responsive writing pedagogy.

Introduction

Every so often, you stumble upon an article that you recognize will significantly influence not only your own endeavors but also the broader field in which you are involved.

Occasionally, you come across a publication that not only elucidates critical terminology essential for comprehending multifaceted phenomena but also delivers comprehensive analyses, evidencing the applicability of these concepts within real-world contexts.

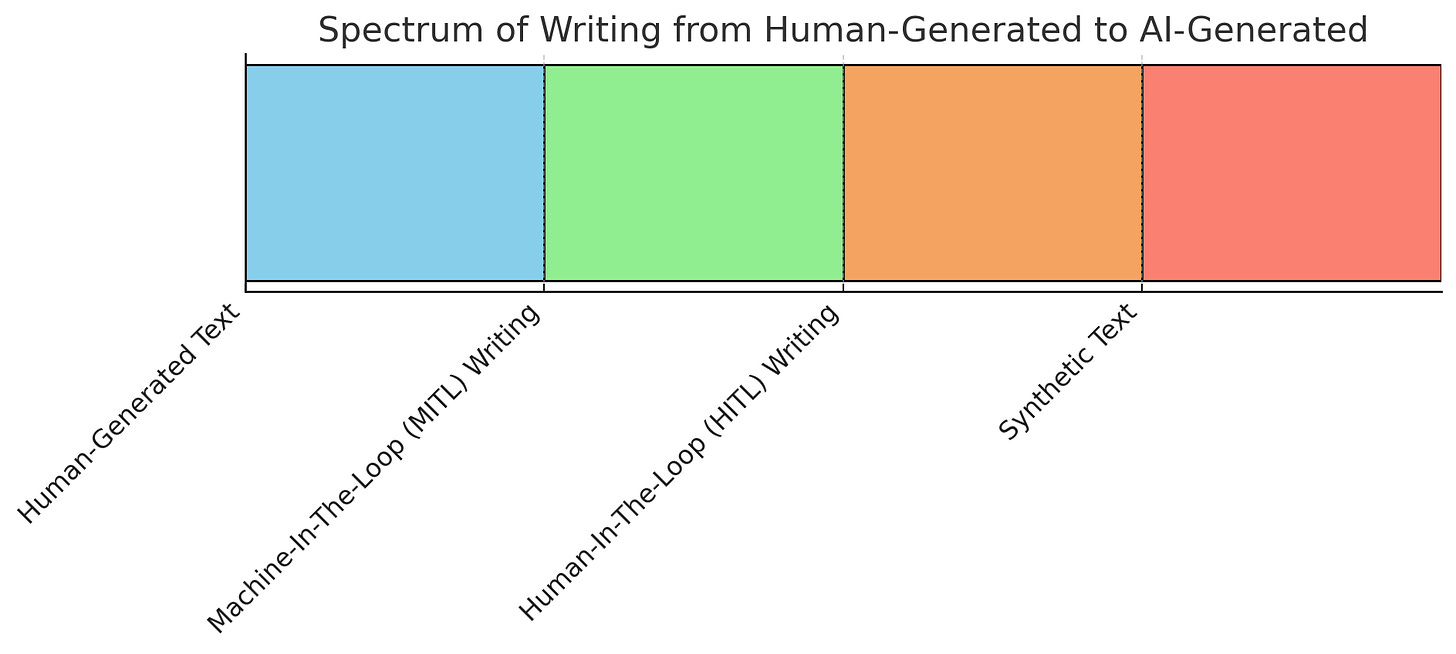

A month ago, I read a post by Kimberly Pace Becker from Academic Insight Lab, which reflected on a noteworthy publication by Alan Knowles. His article, "Machines-in-the-loop: Optimizing rhetorical load," featured in Computers and Composition, a journal that is quickly becoming one of my favorites. In his work, Knowles conducts a detailed analysis of the spectrum between "synthetic" and "human-authored" writing, examining the unique capabilities and distinctions of the various forms of writing that exist within this continuum.

Realizing the significance of his study, I reached out to Alan to inquire if he would be interested in contributing to an article dedicated to exploring his research. To the benefit of the Educating AI community, he agreed. Without further delay, let's delve into unpacking this important contribution to the emerging field of AI-responsive writing curriculum.

Author Introduction

I am excited to introduce Alan Knowles to the readers of Educating AI. Alan is an amazing Instructor of Professional and Technical Writing and the Director of Writing Programs at Wright State University. Currently, as a PhD candidate in Rhetoric and Composition at Miami University (Oxford), his research is pioneering in the fields of digital rhetoric, emerging writing technologies, and human-AI collaborative writing processes.

In addition to his academic and research endeavors, Alan has significantly contributed to educational development through his roles at Miami University (Oxford). He served as the Director and prior to that, Associate Director of the Portfolio Program within the Department of English. In these capacities, he was instrumental in managing the program that allows incoming students to earn credits for the First-Year Writing course through portfolio assessment. His leadership involved coordinating the creation and dissemination of informational materials, overseeing the assessment process, and directly supporting students and assessors alike.

Alan's comprehensive background, combining hands-on educational leadership with innovative research, positions him as a valuable contributor to discussions on AI-responsive writing curriculum, enriching our understanding and practices in this evolving field.

Article Distillation

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S8755461524000021

Alan Knowles' insightful article delves into the evolving relationship between humans and artificial intelligence (AI) in the context of writing, with a spotlight on technical and professional communication. By examining the emergence of ChatGPT and its parallels with historical technological advancements, Knowles challenges traditional notions of authorship, introducing concepts like AI Collaborative Writing (AICW) and Rhetorical Load Sharing (RLS). These concepts advocate for a nuanced view of authorship that transcends the binary classification of texts as purely human or entirely AI-generated.

Knowles reimagines the classical rhetorical process for the digital age, proposing a collaborative model where AI enriches human creativity across invention, arrangement, style, memory, and delivery. This model suggests AI can assist in brainstorming, structuring ideas, crafting language, enhancing argumentative depth, and optimizing digital delivery, all under human guidance.

Through fictional scenarios, Knowles illustrates the spectrum of AI integration in writing. Damon’s minimal human intervention approach, or Human-In-The-Loop (HITL), contrasts with Paige's balanced Machine-In-The-Loop (MITL) method, where AI serves as a supportive tool rather than a substitute for human effort. These examples not only highlight the practical application of Knowles' theories but also emphasize a collaborative model that amplifies human creativity and agency.

In his teaching, Knowles embodies these principles, using AI to enhance rather than replace the creative process. The fictional stories of Damon and Paige exemplify how AI can be integrated into education to foster creativity and critical thinking, advocating for a thoughtful approach that equips students for a future of collaborative writing with AI. This vision champions a symbiotic relationship between technology and human potential, aiming to elevate the rhetorical skills and understanding of students in an AI-integrated world.

Key Terminology

Machine-in-the-loop (MITL) = Human > AI Human-in-the-loop (HITL) = AI > Human

A crucial aspect of Alan Knowles' work is his establishment and organization of terminology related to the AI-enhanced writing process. Below is a glossary of key terms and definitions he proposes for use, aimed at fostering clear dialogue among educators and professionals seeking to integrate AI into contemporary classrooms and workplaces.

AI Collaborative Writing (AICW): Writing processes that involve collaboration between human authors and AI technologies, spanning a spectrum from human-authored to synthetic texts.

Rhetorical Load Sharing (RLS): A framework for understanding how the rhetorical tasks in writing can be shared between humans and AI, based on the traditional canons of rhetoric.

Human-In-The-Loop (HITL) Writing: A writing process where human involvement is essential at key points, especially in the final stages, to ensure ethical and quality outcomes.

Machine-In-The-Loop (MITL) Writing: A model of AI collaborative writing where the AI acts more as an assistant than a co-author, with humans retaining the majority of the rhetorical load.

Synthetic Text: Text generated by AI that has not been significantly edited or fact-checked by a human, raising ethical and quality concerns.

Human-generated Text: Text created through the direct intellectual and creative efforts of individuals without the assistance of generative AI technologies.

Interview

Redefining AI Integration with Rhetorical Load Sharing (RLS):

How does RLS innovate our approach to AI in writing, particularly in enhancing creativity and critical analysis in technical and professional communication?

In general, I would recommend that all writing professionals learn to train large language models (LLMs) via few-shot learning, a process that allows users to provide a few input/output samples to the AI before asking it to generate its own text. This allows writers to leverage their own expertise to get better results out of LLMs. For seasoned professionals, this could mean utilizing troves of prior work as LLM training data.

For example, a technical writer whose work often involves explaining technical concepts to non-technical audiences could format their work few-shot samples by formatting technical documents as inputs and the public-facing texts they wrote to explain those documents as outputs.

Put simply, this is like telling the LLM, “if I were to give you this technical document (input), I would want you to generate this public-facing text (output).” Training LLMs in this way makes them much more useful in a professional writing workflow. And no need to stop at using a single few-shot training LLM in a workflow – mapping out larger workflows that include multiple few-shot trained LLMs is where things get interesting, and where user creativity comes into play.

Adapting Writing Pedagogy in an AI-Augmented Environment:

With the growing presence of AI tools like ChatGPT in education, what pedagogical strategies do you recommend to cultivate critical writing skills amidst AI's influence?

While I am very optimistic about the potential benefits of LLMs for writing professionals and students, it is important to understand that these tools have serious limitations. A primary benefit of LLMs is the potential reduction of labor required for writing, but in the hands of untrained users, there is a real risk that this labor reduction occurs at the expense of writing quality, including the generation of text that is factually inaccurate, a phenomenon often referred to as AI hallucination. Because of this, there is a serious need for students to develop new types of AI-specific critical reading skills in order to be able to more safely collaborate with LLMs.

To drive this point home, the first AI activities in my courses tend to focus on exploring the limitations of the tools. In one activity, I assign a common reading in the course and have my students write up some sort of analysis of the text before class (the text should be published pre-2019 so there is a chance it was used in GPT’s training data). Then, during class, we discuss the students’ analyses of the text, noting important points of agreement between students.

By this point, students should be familiar enough with the text to be able to point out errors in the way others discuss it. Next, we prompt an AI tool like ChatGPT to generate an analysis of the same text. At first, students tend to be very impressed by the generated analysis, but upon closer inspection, they usually find some strange errors – inaccurate quotes or paraphrases, analytical claims that students unanimously disagree with, etc.

The Future of Professional Writing Amidst AI Advancements:

As AI becomes adept at complex writing tasks, what future dynamics do you foresee for professional writers and technical communicators to keep their skills relevant?

At some point, professional writers who use LLMs will replace those who do not. This isn’t because LLM users are somehow better writers, but because they will simply have a higher output than those who do not use LLMs. The rationale for employers seems obvious -- why hire a grant writer who can write 1 grant proposal per week when there are grant writers (who collaborate with LLMs) who can write 3+ grant proposals per week?

However, not all writers who use LLMs are the same. AI collaborative writing is a new type of writing that requires practice to improve. To get better at using LLMs, it is essential that writers begin thinking about text as data. This is true when doing basic things like writing prompts for LLMs or reading/editing text generated by LLMs. These technologies are, at the most basic level, input/output machines that detect and reproduce patterns in text data.

As such, professional writers should start treating their own writing as data to be leveraged for future AI collaborative writing use cases. Your text data will almost definitely be used by companies (without your permission) to improve their technologies. It should also be used by you, to your own advantage.

In my writing courses, I require students to practice process-oriented writing (i.e., outlines, rough drafts, and revisions) and strongly advise students to save all these instances of their writing on a secure storage device. Having this data later may be tremendously useful, as it could allow them to train LLMs on their own writing samples to transform their writing from one stage to the next in a style/voice that is much closer to their own than any text generated by a base LLM model would be. This is advice I would also give to professional writers. No matter how insignificant a draft of a project may seem to be, save it somewhere; it could prove to be valuable data later that, if used correctly, will allow you to get much more out of AI writing technologies.

AI's Contribution to Creativity in Writing:

Can AI genuinely enhance the creative writing process, or does it risk stifling originality by rehashing known ideas? How should we evaluate creativity in AI-generated outputs?

My area of expertise is not in creative writing, so I cannot claim to have much authority on this. So, here are a few thoughts from an outsider:

Hallucinations, which are the most concerning thing about LLMs for technical or academic writing, might be thought of as more of a feature than a bug in creative writing situations where strict adherence to facts is not a concern (i.e., fiction writing).

It is not difficult to imagine a divide between creative writers who use LLMs and those who refuse to do so, as similar digital vs traditional fights have happened with many prior technologies. There is still a long-standing feud between some artists who only use the canvas and artists who use digital technologies, with the former labeling the work of the latter fake or inauthentic. However, as anyone who has attempted to create digital art knows, it takes lots of hard work and creativity to make high quality digital art, despite the type of work required to do so being meaningfully different.

Creating digital art is a unique skill set that must be developed. The same is true of using AI for creative or technical writing – it is a new, unique skill set that must be developed, and while it may change the nature of the work, it does not remove the need for the human collaborator to possess creativity or an expertise about creative writing practices. Like in the case of digital art, this is evidenced by some writers who use AI being able to create texts that are much better than the texts created by others who use AI.

Assessing AI-Generated Writing:

What criteria do you propose for evaluating the quality of AI-generated content, ensuring its effectiveness across diverse contexts?

From my perspective as an educator and technical writer, the most important quality of AI collaborative texts is that they, at minimum, include a human-in-the-loop (HITL) at the final stage of the writing process. That is, that before a generated text is published, or submitted for a grade, the human collaborator must thoroughly edit/proofread the text. As I have mentioned a few times, AI hallucinations are a serious issue in technical or academic texts. If there are inaccuracies in a generated text, they must be corrected by the human user. If not, the human user is solely responsible for those inaccuracies, not the AI.

In my role as an educator, I push students beyond this baseline HITL writing to what I consider to be a more ideal, and more involved machine-in-the-loop (MITL) writing workflow, in which students retain majority of the rhetorical load. Assessing this type of writing involves evaluating the text itself as well as the writing process as reported by the students. I ask student to submit a brief rationale with their AI collaborative texts that explains how the AI tools were used, why they were used in such ways (i.e., what the student hoped would come of it?), and how useful they were when used this way (i.e., did the AI help in the way the student hoped it would?).

I am always careful to describe this rationale requirement as a useful practice for students to improve their AI collaborative writing processes, not as a form of teacher surveillance. I think it is extremely counterproductive to create an adversarial relationship with students by suggesting that I am out to label them as cheaters for using AI the wring way, so I make sure they know this is my position.

Also, I have never used AI-text detectors on my students’ work, and I strongly suggest no one else does. This is not only unethical – potentially a FERPA violation considering how little we know about what these companies will do with the text data we give them – but also unproductive, as AI text detectors DO NOT work. I have done experiments with upper-level students in which we were able to fool these detectors into labeling purely synthetic text as human-authored at a nearly 100% rate, and far more concerning, the detectors regularly give false positives, which will continue to lead to very consequential, false accusations of cheating against students.

Ensuring Equitable Access to AI Writing Tools:

In promoting accessible AI benefits, what measures can ensure all students, regardless of their socio-economic background, gain from AI writing tools without exacerbating the digital divide?

Fortunately, the most popular generative AI tools still have free-to-use versions. However, there are also premium versions of these available, which perform better and sometimes have significant features that the free versions do not, such as image generation for the premium version of ChatGPT, which is not available in the free version. There is also an emerging open-source ecosystem of generative AI tools, so there is potential that those will advance enough to provide long-term access to those who cannot afford premium subscriptions.

If free tools remain available, the biggest barrier to equitable access will be educational institutions that ban usage. It is unlikely, for example, that elite private institutions will do this considering the competitive advantage experience with these tools would give their students after graduation, which these institutions would benefit from in their reporting of job placement, admissions to universities or grad schools, etc. What concerns me is the potential for the most restrictive generative AI policies to be implemented in underfunded public schools in attempts to root out “cheaters.” If only the students who come from the most well-funded schools have access to and training with generative AI technologies, existing socio-economic gaps in the US and abroad will only widen.

Alternatively, these technologies could help to reduce these gaps. Writing skills have always served a gateway function in higher education and industry. If there is equitable access to generative AI tools going forward, maybe less people will be denied access, and the potential for social mobility will increase.

Balancing AI Use with Skill Development:

Specifically for grades 7-12, where foundational writing skills are crucial, how do you envision balancing AI tool usage to support rather than supplant essential skill development?

I don’t imagine most elementary or middle schools will incorporate generative AI technologies in their curriculum any time soon, and that is probably for the best. There is a base level of writing and reading skills required to be able to use generative AI tools like LLMs effectively. However, we know that many people will graduate high school and never pursue higher education, so I do think it is important that high schools begin incorporating AI into their curriculum to some degree.

As I explain in my article, one of my biggest concerns about LLMs is that uninformed users will not be suspicious of the veracity generated text and will either contribute to a wave of digital misinformation (i.e., internet flooded with AI hallucinations by unwitting users with no malintent) or will make important decisions based on bad info received from LLMs. The writing classroom may be the only place people will ever get to experiment with generative AI with the oversight of an authority figure who insists that they use them ethically and critically.

Also, it is worth noting that we simply do not know what impact using LLMs will have on the development of writing skills. There is no data on this, yet so all claims about what will happen to young writers are pure speculation. This speculation is important in the early days of such a transformative new technology, but we should be careful not to draw foregone conclusions. There is obvious potential for good and bad, here.

The bad. It is possible that being introduced to generative AI too early in one’s education is detrimental because students will not see a need to develop their own writing skills. Might LLMs be bad for writing development for the same reason paper mills are bad for writing development? Or for the same reason young students having their parents write their essays is bad for their development?

The good. It is possible that early introductions are beneficial because LLMs near-instantly show students examples of what their ideas could look like if drafted as full prose. Perhaps LLMs will have benefits like having a lifelong private tutor?

Key Takeaways

Here are the 6 key takeaways from Alan Knowles' responses:

Writing professionals should learn to train large language models (LLMs) via few-shot learning, leveraging their own expertise and prior work to get better results. Mapping out workflows that include multiple few-shot trained LLMs can lead to interesting and creative applications.

Students need to develop new types of AI-specific critical reading skills to collaborate with LLMs safely. Educators should focus on exploring the limitations of AI tools to help students understand the potential for factual inaccuracies or "AI hallucinations."

Professional writers who use LLMs effectively will likely replace those who do not, as they will have a higher output. AI collaborative writing is a new skill that requires practice, and writers should start treating their own writing as data to be leveraged for future AI use cases.

The most important quality of AI collaborative texts is that they include a human-in-the-loop (HITL) at the final stage of the writing process to ensure accuracy. Educators should push for a more involved machine-in-the-loop (MITL) writing workflow, where students retain the majority of the rhetorical load.

Equitable access to AI writing tools is crucial to prevent the exacerbation of the digital divide. If only students from well-funded schools have access to and training with generative AI technologies, existing socio-economic gaps may widen. Alternatively, these technologies could help reduce these gaps if there is equitable access.

Most elementary and middle schools may not incorporate generative AI technologies in their curriculum soon, which is probably for the best. However, the impact of using LLMs on the development of writing skills and other important competencies is unknown, and speculation about potential outcomes should be made with caution, as there is no data available yet.

I'd like to thank Alan for sharing his extensive knowledge and valuable insights on integrating AI in writing and education. His thoughtful responses have provided a solid foundation for developing AI-responsive pedagogy in today's classrooms. Alan's contributions will undoubtedly help educators navigate the challenges and opportunities that AI brings to the field of writing, and we appreciate his generosity in sharing his expertise.

Nick Potkalitsky, Ph.D.

Great article and interview! As a middle school teacher, I try not to play up AI too much, lest I summon the Streisand Effect. I will say, however, that my corporation has Grammarly installed on devices. No big deal. Until the day *they* added AI elements, and suddenly some students start generating professional sounding prose. That has been tricky.

I've also talked to students about hallucinations. I remind them that certain texts are not in data sets, and AI cannot therefore just spout out answers. I mean, it *can*, and it'll be obvious. That said, I'm thankful they still cheat uncritically the old fashioned way: Copying whatever Google says whether it's right or wrong.

But as for the impact on the K12 classroom, there are teachers on Substack. Ask away!

Thanks for this deep dive interview, Nick!

I like Alan's sober and well-considered look at AI - focusing on its potential while acknowledging the many shortcomings. The approach of working through a text yourself and then comparing AI output is the perfect way to ease someone unfamiliar into AI while exposing the pitfalls like hallucinations, etc.

And I tend to agree that hallucinations are less critical when it comes to creative writing and brainstorming. In fact, they may actually nudge your thinking into an unexpected and fun direction.

Thanks for sharing your thoughts Alan!