The Long Game: Why AI Implementation Is a Rebuild, Not a Rollout

We are in the middle of a 3-5 year rebuild. Anyone offering easy solutions hasn’t come to grips with the full complexity of what we’re facing.

The response to my post about the Claude Soul Document was revealing. Some readers saw it as an endorsement of Claude. Others recoiled at Anthropic and their machinations. Such moments remind me why I do this work on Substack. Between these diverging views sits an abiding tension worth exploring. Mike Kentz’s recent post captures more of this same complexity.

I am offering a 20% Forever Discount to readers who sign up for a yearly paid subscription before the end of the year. Thanks for all the support over the years. Together we are creating a very special collaborative community.

This past Friday, I presented to the Ohio 8 Coalition—superintendents, tech directors, and union presidents from Ohio’s nine largest urban districts, including Cleveland, Columbus, Akron, Cincinnati, Dayton, Canton, Lorain, and Youngstown. This wasn’t another AI hype session. This was a room full of leaders responsible for hundreds of thousands of students, grappling with a disruption they didn’t ask for and a legislative deadline they can’t ignore.

My main message: We are in the middle of a 3-5 year rebuild. Anyone offering easy solutions hasn’t come to grips with the full complexity of what we’re facing.

The Legislative Clock Is Ticking

Ohio’s House Bill 96 requires every district to adopt an AI policy by July 1, 2026. The Ohio Department of Education and Workforce must publish a model policy by the end of this month. Most districts are somewhere between reactive and compliance-focused—policy frameworks exist, committees have formed, but clear instructional guidance remains absent.

Here’s what I told them: This deadline is not just an obligation. It’s an opportunity.

Not an opportunity to check a box. An opportunity to build a comprehensive guidance document that winnows down the flood of AI tools into a robust, actionable system. If we’re not getting student data across chats—not just inside single chats—we’re greatly underutilizing these tools. We’re experimenting without purpose, without the ability to gauge success.

Four Foundational Shifts We Can’t Avoid

1. Instructional Redesign: The New Starting Point

Here’s the foundational premise: Any work sent outside of class will be completed with the assistance of AI.

Any other starting point is a fool’s errand at this point.

This isn’t pessimism. It’s pragmatism. We need to go beyond AI assessment scales and rubrics that try to police student use. AI is a highly interactive medium of learning—it’s genuinely hard for students to stay inside a “permissible editing modality” when AI continually and unpredictably prompts them toward other kinds of engagement.

The solution isn’t more restrictions. It’s redesign. Chat rooms need to be set up that focus only on assigned purposes. Those engagements need to happen in the classroom, then be closed down when students leave. We need to accept that homework as we’ve known it has fundamentally changed.

2. Assessment Redesign: Naming the Crisis

We are in a crisis moment. Many teachers simply do not know what students know anymore.

We have two possible pathways:

Go all in with AI: Adopt robust systems that serve as open engagement platforms where learning is proven through punctual, demonstrable moments of competency.

Lean seriously into process pedagogy: Make the thinking visible, scaffold the journey, assess the learning process itself.

But more importantly, we need to globally decide what it is important for students to know.

I’m impressed by a small school in Connecticut that started assessment redesign with the premise that authority and research are essential parts of student wellbeing. They’re dynamically redesigning an entire assessment system centered on that value.

In public districts, we don’t have that luxury of starting from scratch. State standards and state testing serve as punctual moments where students must demonstrate different kinds of knowledge in circumscribed, non-AI-assisted formats. Until these structures give way—and they won’t, not for 10-20 years—we will continue to have to design and redesign assessment to guide students toward success in these formats.

We can dream about ideal schools where work flows from genuine engagement, where learning happens entirely through authentic real-world situations or design cycles or PBL. I love those dreams. I was one of those dreamers. But when working with the Ohio 8 Coalition, my pragmatism reignited. Our AI response plan needs to build out of the crucible of what is actually happening in schools today.

3. Purposive Technological Ecosystems: Discernment Over Accumulation

Districts are drowning in AI tools. Every edtech company is slapping “AI-powered” on their pitch deck. The result is chaos—teachers don’t know what’s approved, students toggle between platforms, data sits in silos, and no one can assess what’s actually working.

We need discernment of purpose. What are we trying to accomplish? What student data do we need to see that progress? What tools genuinely serve those purposes, and what tools are just adding noise?

This is where the policy deadline becomes an opportunity. Build a guidance document that doesn’t just say “be ethical with AI.” Build one that says: “Here are the three AI systems we’re using district-wide. Here’s what each one does. Here’s when students should use them. Here’s what teachers can see. Here’s how we’re protecting data.”

4. Teacher-Led Curriculum Rebuilding: Top-Down Meets Bottom-Up

I presented initial findings from my disciplinary AI cohort—work happening right now in central Ohio where teachers are rebuilding curriculum together across content areas. The idea is simple: complement top-down trainings (PD days focused mostly on tools) with emergent teacher cohorts rebuilding curriculum from the ground up.

This sparked a fire in several districts.

Why? Because teachers continue to be the superpower during this AI disruption.

Too many caricatures are circulating right now about teacher responses to AI—that they’re either luddites resisting change or reckless early adopters abandoning rigor. The truth is far more complex. Each teacher is grappling with a complexity they never asked for, making difficult decisions with no clear assurance of success, all for the best interests of their students and communities.

As my colleague Mike Kentz and I have said: teachers will continue to be the drivers of change over the next 5-10 years. Any AI implementation plan that doesn’t account for their wisdom will not likely have much success.

What I Learned in That Room

The Ohio 8 Coalition represents some of the most complex, under-resourced, high-need districts in the state. They don’t have the luxury of small class sizes or experimental pilot programs. They have real constraints: state testing, tight budgets, teacher shortages, union contracts, board politics, community skepticism.

And yet, the conversation in that room was one of the most hopeful I’ve experienced in months.

Not because anyone pretended this would be easy. But because the leaders present understood that this is a rebuild, not a quick fix. They understood that rushing to compliance without instructional clarity would waste this moment. They understood that the students most vulnerable to AI’s risks—students with IEPs, students in high-poverty schools, students already disconnected from adults—deserve more than policy theater.

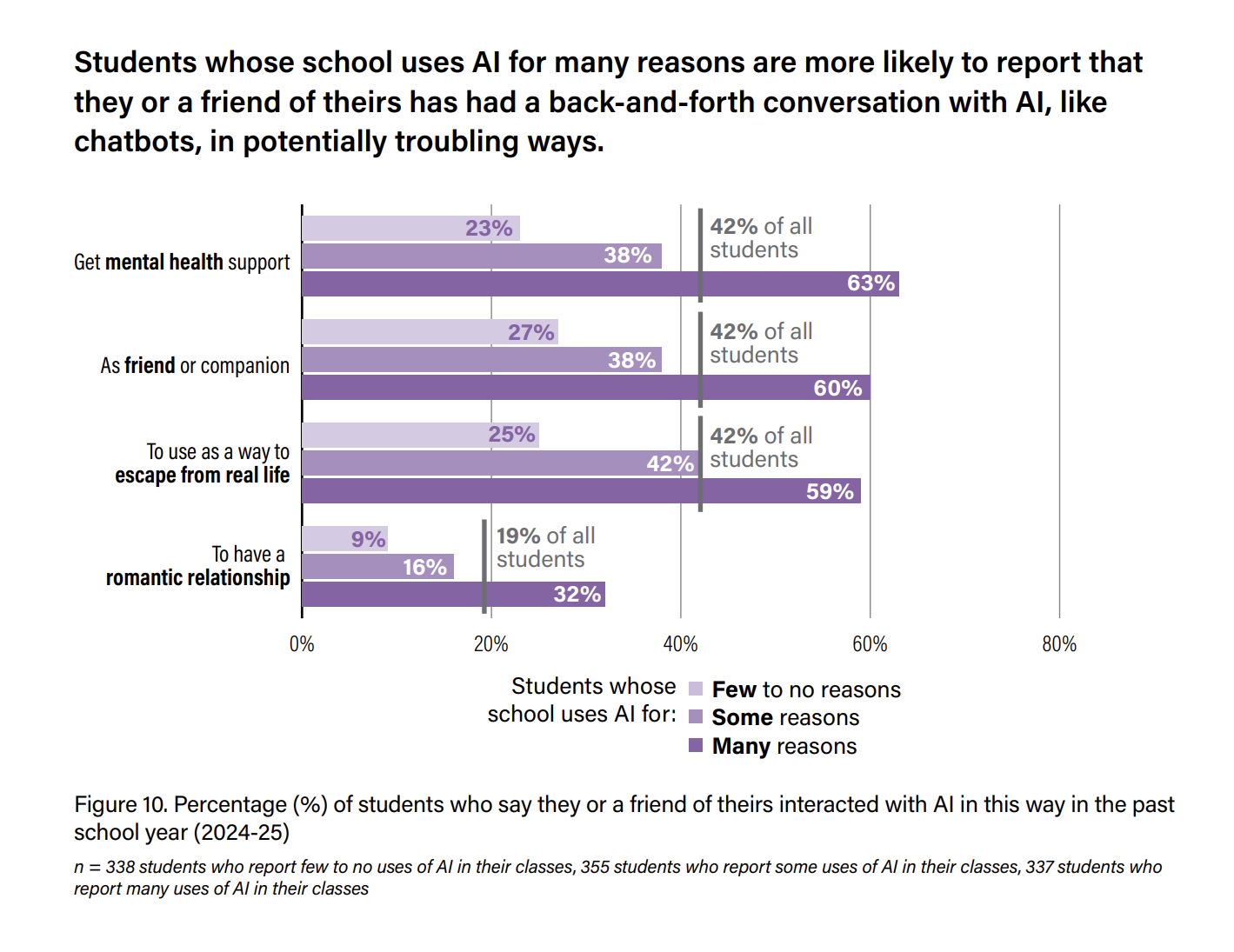

We talked about the data: 71% of teachers worry about student emotional dependence on AI. 52% of students in high-AI schools feel less connected to their teachers. 42% of students are using AI for mental health support, often with no adult awareness. 36% of students are aware of AI-generated deepfakes at their schools.

One finding from the Center for Democracy and Technology’s recent report stopped the room: in high-AI districts, students use AI as a companion at double the rate of low-AI districts (63% versus 25%). The same pattern holds for mental health support.

I’ll return to this report in an upcoming article for a deeper dive, but what struck most folks in the audience wasn’t a call to retreat from AI in curriculum. It was a recognition that our current approach (everyone does their own thing, often without adequate training or framing in terms of AI literacy, in the absence of a scope and sequence that defines what kinds of access are developmentally appropriate) is contributing in some way to these outcomes. The solution isn’t less AI. It’s more intentional implementation.

These aren’t abstract futures. These are present realities happening in districts across Ohio right now.

The Path Forward

Ohio districts have until July 2026 to adopt a policy. That’s seven months.

But the real work—the instructional redesign, the assessment reimagining, the purposive technology ecosystems, the teacher-led curriculum rebuilding—that’s a 3-5 year project. Minimum.

Here’s what I’m asking districts to consider:

Use the policy deadline to build something comprehensive. Not just a compliance document. A living guidance framework that addresses instruction, assessment, wellbeing, equity, and data governance.

Start with instructional redesign. Accept that homework has changed. Design for that reality, don’t fight it.

Get serious about assessment. What do students actually need to know? What can we let go? What must we redesign?

Build teacher cohorts. Top-down training alone won’t work. Teachers need time, space, and support to rebuild curriculum together.

Center the most vulnerable. If your AI plan doesn’t explicitly address students with IEPs, students in poverty, and students already disconnected, it’s not a plan—it’s a hope.

The shift is happening whether we’re ready or not. How we navigate it is up to us.

I left that room grateful—grateful to work with districts doing the hard, unglamorous work of real transformation. Not the Silicon Valley version. The version that happens in classrooms with 30 students, limited budgets, and state tests that still matter.

That’s the work that will determine whether AI becomes a tool for equity or another mechanism of disparity. And that work doesn’t happen in 90 days. It happens over years, with teachers at the center, guided by leaders willing to name the complexity and commit to the rebuild.

Nick Potkalitsky, Ph.D.

Check out some of our favorite Substacks:

Mike Kentz’s AI EduPathways: Insights from one of our most insightful, creative, and eloquent AI educators in the business!!!

Terry Underwood’s Learning to Read, Reading to Learn: The most penetrating investigation of the intersections between compositional theory, literacy studies, and AI on the internet!!!

Alejandro Piad Morffis’s The Computerist Journal: Unmatched investigations into coding, machine learning, computational theory, and practical AI applications

Michael Woudenberg’s Polymathic Being: Polymathic wisdom brought to you every Sunday morning with your first cup of coffee

Rob Nelson’s AI Log: Incredibly deep and insightful essay about AI’s impact on higher ed, society, and culture.

Michael Spencer’s AI Supremacy: The most comprehensive and current analysis of AI news and trends, featuring numerous intriguing guest posts

Daniel Bashir’s The Gradient Podcast: The top interviews with leading AI experts, researchers, developers, and linguists.

Daniel Nest’s Why Try AI?: The most amazing updates on AI tools and techniques

Jason Gulya’s The AI Edventure: An important exploration of cutting-edge innovations in AI-responsive curriculum and pedagogy

Search, and now AI, has changed what we use our minds for. Education was once learning passages by heart, like an actor with play scripts. Now it should be about how to find details using some key waypoints. At some point in the not-too-distant future, the interface to the global knowledge base is going to be direct from the brain, no screen and keyboard, except to extract media. So what we will want is move from learning to write and memorizing key points to answer essay questions or select multiple-choice answers, to understand how to do some things and und understand teh whys and meaning of knowledge.

The constraint of education policies is going to be a problem, as it will demand the memorization of "how-to", and facts, rather than the real value of knowledge, which is understanding. Most of us forget the facts that were crammed into us in K-12. Hopefully, we retain enough facts to be able to navigate our way in teh ocean of knowledge, like recalling a few key locations when navigating without a map or GPS. We will need the skills to select quality information from mis- and disinformation, a skill that will remain useful throughout our lives, and likely supported by software tools to help with this.