Thinking With Tools: David Winter’s Typology of Assistive Tool Use (TATU)

How Our Conceptual Frameworks for AI Use Shape Our Actual Practice

If you find value in our work at Educating AI and want to help shape the future of AI education and awareness, consider becoming a paid subscriber today. To make it easy, we’re offering a forever 20% discount through this special link:

Your support directly helps us broaden our reach and deepen our impact. Let’s build this together.

Introduction

by Nick Potkalitsky

In recent years, the relationship between humans and AI has evolved rapidly. No longer relegated to simple task automation or rote computation, AI systems have become increasingly embedded in our everyday cognitive processes — from writing and designing to decision-making and problem-solving. Yet, while their capabilities expand, our collective understanding of how to work alongside these tools in a thoughtful, strategic, and reflective manner has often lagged behind.

Much of the discourse around AI use focuses on outputs: how to get better ones, faster. What is less discussed — and urgently needed — is a robust framework for thinking about the process of interaction itself. How should individuals engage with AI systems in ways that enhance their own thinking, rather than merely offload it? How can the human side of the partnership remain dynamic, critical, and evolving as these tools become more sophisticated?

Enter David Winter. David Winter serves as Head of Research & Organisational Development at The Careers Group, University of London, where he directs research activities and professional development for careers services across University of London colleges. A Fellow of NICEC and former AGCAS Learning Director, David combines extensive experience as a careers consultant with expertise in training and strategic development to enhance employability service delivery.

Winter’s work on assistive cognition offers a structured and nuanced approach to answering these questions. His Typology of Assistive Tool Use (TATU) is not a how-to guide for prompt engineering or productivity hacks. Rather, it is a developmental model — one that maps out various levels of sophistication in AI-human interactions, and charts pathways for progressing through them. Importantly, Winter’s typology acknowledges that individuals may move both upwards (from simple to complex uses) and downwards (from exploratory thinking to refined outputs), depending on context and experience.

In this longform post, I will present Winter’s typology in his own methodical language, preserving the clarity and rigor of his categories and descriptions. Following that, I will reflect briefly on why this model may offer valuable insights for anyone seeking to move beyond transactional uses of AI toward richer, more dialogic and transformative engagements.

What follows, then, is David Winter’s framework, unaltered and in his own terms. David kindly helped with the preparation of this manuscript, adding editorial notes and supplying his amazing graphics!!!

Nick Potkalitsky, Ph.D.

Overview of David Winter’s Typology of Assistive Tool Use

(by Nick Potkalitsky)

Before presenting the full details of David Winter’s approach, it is helpful to briefly orient ourselves to the overall structure of his typology.

Winter’s model is built around the idea that individuals engage with assistive tools at varying levels of sophistication. These levels are not fixed, nor are they necessarily linear. Instead, users may progress gradually through them, revisit earlier stages, or approach them strategically depending on their familiarity with the tool and the nature of the task.

The Typology of Assistive Tool Use (TATU) is organized into four distinct levels. Each level represents a different way in which an individual may relate to the tool — from seeing it primarily as a means of generating outputs, to engaging with it as a critical friend and collaborative thinking partner.

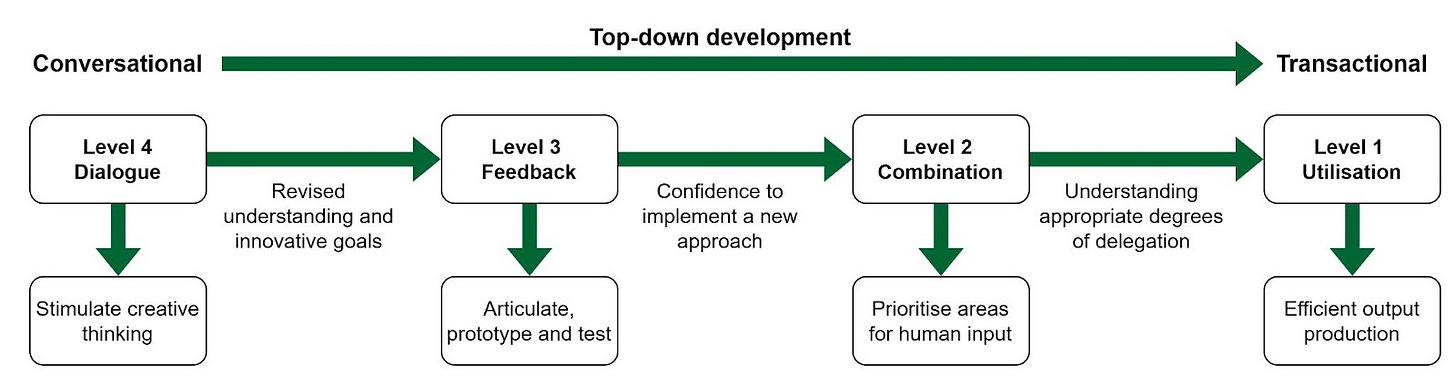

In addition to defining these four levels, Winter describes two fundamental developmental pathways:

A bottom-up approach, where individuals move from simple, transactional uses of the tool to more complex and dialogic interactions.

Figure 1. Bottom-up development.

A top-down approach, where individuals start with advanced conceptual engagements and progressively channel them into more structured and practical outputs.

Figure 2. Top-down development.

What follows is Winter’s methodical presentation of these levels and pathways, using his precise language to describe the development outcomes, processes, and considerations associated with each stage.

David Winter’s Typology of Assistive Tool Use

Bottom-up (transactional to conversational)

This journey takes the individual through increasing levels of sophistication in tool use, which involves a progression from convergent thinking to divergent thinking. It might be best suited to someone who is inexperienced in using the tool and/or inexperienced in the task. However, careful scaffolding of learning and guided reflection may be required to ensure that the individual doesn’t get stuck at the lower levels of tool usage.

Level 1 Utilisation

Development outcomes

The individual starts by viewing the tool primarily as a means for generating outputs. The relationship between the human and the tool is transactional offloading — the tool’s purpose is to do the work for the individual.

Development within Level 1 consists of refining human inputs to get more suitable outputs from the tool. This involves critically evaluating the tool’s outputs against the task requirements (criteria-based evaluation).

Progression from this level requires the individual to develop a critical awareness of the strengths and limitations of the tool across various tasks.

The process

The individual is given a variety of tasks (different types of task and/or variants of the same task).

They interpret the task requirements to create instructions for the tool to generate task outputs.

They evaluate the tool’s outputs against the task requirements.

If the outputs do not meet the requirements, the individual identifies and prioritises the discrepancies.

They then re-apply or re-interpret the task requirements to create modified instructions and try again (iteration).

If the outputs meet the requirements, the individual reflects on what they have learnt about the relationship between tool inputs and outputs and the strengths and limitations of the tool.

The individual moves on to the next task or the next variant of the same task.

Inputs

Task requirements

For this Level, tasks should be relatively simple, at least to begin with. As individuals develop, task complexity can be increased in order to start progression towards Level 2 development.

For inexperienced users, task requirements could include explicit criteria or detailed rubrics to be used in the evaluation of outputs. They could also be provided with one or more example task outputs for comparison alongside the criteria.

More confident users might be asked to establish their own criteria in advance (anticipatory) or to identify and articulate the criteria as part of the iterative process (emergent).

Instruction modifications

Inexperienced users could be provided with guidance or suggestions on how to modify tool inputs.

More confident users could be instructed to experiment with different approaches to modification and develop their own guides.

Figure 3. Level 1 Utilization (David Winter)

Further resources

The Rhetorical Prompt Engineering Method developed by Dr Jeanne Beatrix Law is an example of a structured approach to developing Level 1 thinking aimed at producing content for particular audiences.

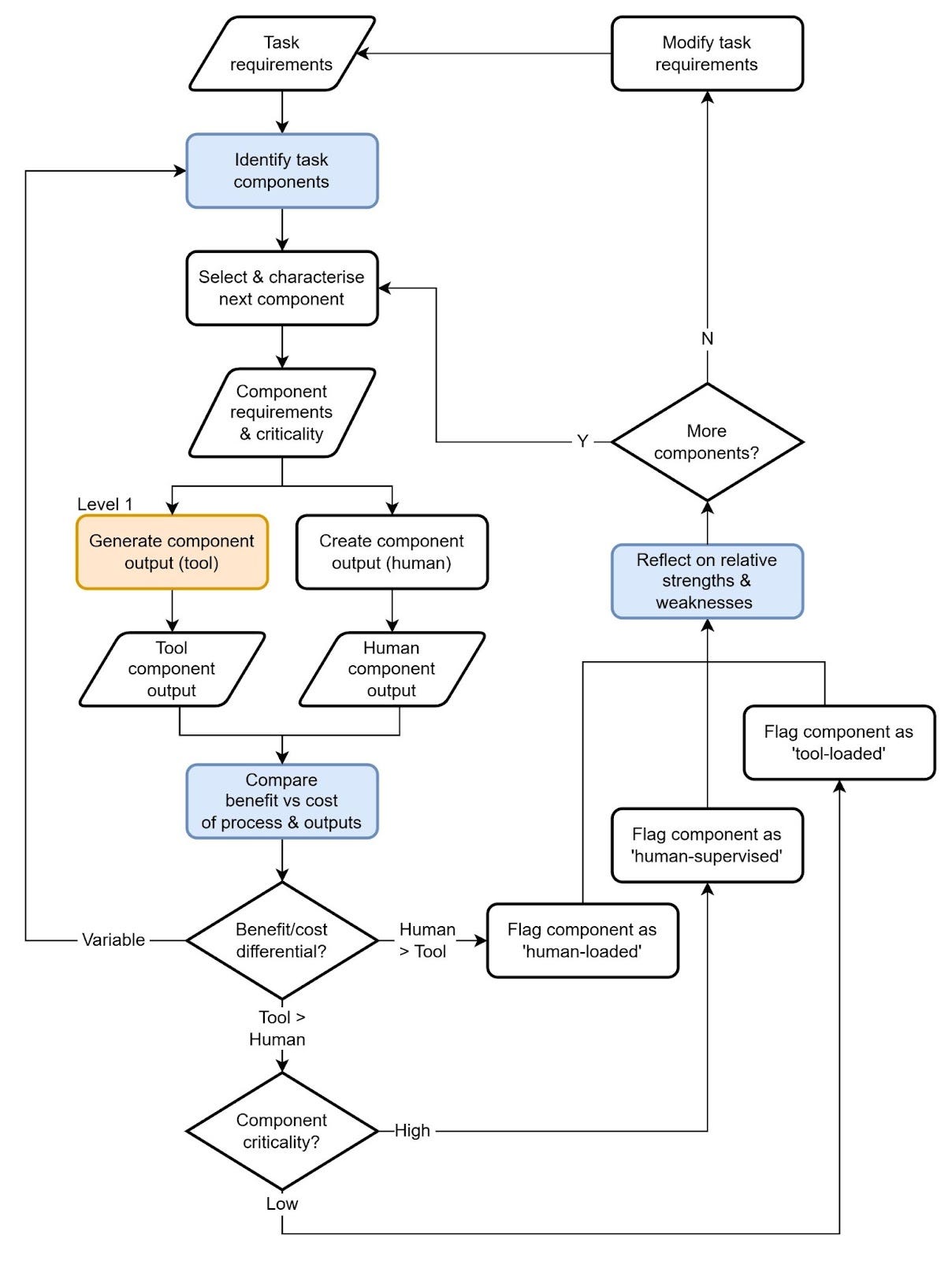

Level 2 Combination

Development outcomes

An individual should progress from Level 1 with an understanding of the tool’s strengths and weaknesses when it comes to generating various types of output. In Level 2, they compare their own abilities with those of the tool. They should develop:

the ability to decompose complex tasks into discrete components

the ability to characterise each component and evaluate its relative importance to the overall task

the ability to evaluate the relative benefits and costs of completing the component oneself compared to having the tool complete it

an understanding of the types of task components that require significant human cognitive input

an awareness of their own strengths and weaknesses in various task components relative to the tool

The process

The individual is given a complex or composite task.

They deconstruct the task into manageable components or sub-tasks.

For each component:

They characterise the component sub-task:

identifying appropriate requirements relative to the overall task requirements

evaluating the relative importance or centrality of the component to the overall task (criticality)

They produce two versions of the required component outputs:

one which they create themselves unaided

one generated by the tool (using Level 1 processes)

They then conduct a comparative cost–benefit analysis of the two outputs and the process by which they were obtained.

Place Image of Process 2

Figure 4. Level 2 Combination (David Winter)

Costs would be the amount of time and cognitive effort required by the individual to produce each output (taking into account any iterations required to improve the output or make it consistent with other components) or the lost opportunity to think for themselves.

Benefits could be:

Extrinsic — e.g. evaluations of quality, accuracy, consistency and appropriateness of the outputs compared to the task requirements and compared to the other component outputs.

Intrinsic — e.g. evaluations of the individual’s gains in learning and confidence from the process, the extent to which the output reflects their authentic voice.

Based on the cost-benefit analysis the individual can identify which types of component should usually be:

human-loaded — requiring the human to take the lead and contribute most

human-supervised — things that can be handled by the tool but which require careful instructions or checking of outputs because they are highly critical to the overall task success

tool-loaded — things that can safely be delegated to the tool with minimal supervision

If the cost-benefit analysis reveals a mixed picture, which favours the tool in some aspects and the human in others, the individual may need to reflect on whether that component needs further deconstruction or characterisation.

The individual reflects on what they have learnt about their own strengths and weaknesses on this component relative to the tool and identifies where they might be able to improve the performance of both.

Sequential co-creation

The parallel output process above allows for direct comparison between human and tool outputs and process on the same task.

In actual tool usage, co-creation may be sequential. Either the individual modifies the output initially generated by the tool, or the individual instructs the tool to amend outputs they have created. (This latter sequence is different from the Level 3 Feedback process in which the tool provides recommendations but the individual is still responsible for evaluating and implementing the feedback.)

Using the tool effectively in this way requires an evaluation of which tasks are best suited to a tool-then-human sequence and which are best suited to a human-then-tool approach. The parallel process should provide individuals with some evidence on which to base this distinction.

In theory, the above parallel process could be extended by adding in a cross-modification element after the initial tool and human outputs.

Inputs

Task requirements

Ideally, the task would be one which is amenable to being decomposed into a variety of components with distinctive characteristics and requirements. For example, some components might require divergent thinking (brainstorming a list of alternatives) whilst others might require convergent thinking (selecting the best option or summarising key points).

Inexperienced users could be given more guidance on how to decompose the task and how to characterise and prioritise task components.

Cost-benefit analysis framework

Individuals could be provided with guidance on the various intrinsic and extrinsic factors to consider in the cost-benefit analysis and appropriate evaluation methods.

Level 3 Feedback

Development outcomes

An individual progresses from Level 1 and Level 2 with an understanding of the relative costs and benefits of having a human or an assistive tool do most of the work on a variety of tasks. In Level 3, they develop an understanding of how to use the tool to support them in enhancing their own work. They should develop:

the ability to construct inputs which elicit appropriate formative feedback from the tool

the ability to evaluate and prioritise the feedback received

an awareness of the strengths and weaknesses of the tool in providing feedback

experience of implementing feedback

the ability to evaluate the extent to which the feedback has improved the output

The process

The individual is given a variety of tasks (different types of task and/or variants of the same task).

They interpret the task requirements and generate their own initial version of the task outputs.

Using the task requirements, they create instructions for the tool designed to elicit feedback on the outputs produced by the individual.

They evaluate and prioritise the feedback produced by the tool against a set of criteria, such as relevance, clarity, specificity, scope, importance, actionability, etc.

They select which elements of the feedback to implement and which to reject.

They make modifications to the outputs based on accepted feedback.

They reflect on the costs and benefits of the process of implementing the feedback.

They are then able to feed the modified output into the tool with instructions for further (ipsative) feedback.

They reflect on any rejected feedback from the tool in order to evaluate the extent to which the feedback instructions could be modified to produce better feedback.

They then reflect on what they have learnt about how best to instruct a tool to give various types of feedback on different tasks.

Figure 5. Level 3 Feedback (David Winter)

Inputs

Task requirements

Tasks should provide opportunities for eliciting different types of feedback from the tool, e.g. content, accuracy, structure, format, style, functionality, conciseness, audience appropriateness, etc.

An alternative initial approach would be to provide some pre-prepared task outputs for the individual to seek feedback on and to modify. However, as the purpose of the typology is to increase the confidence of individuals in their own cognitive processes whilst using assistive tools, it is better to move on to getting the individual to create their own outputs as soon as they have learnt the basics of eliciting feedback.

Tasks should be relatively simple at first to facilitate quick human task outputs but could increase in complexity as the individual gains confidence in their own ability to produce outputs.

Feedback instructions

Inexperienced users could be given guidance on different types of feedback to elicit from the tool.

Further resources

Tips on obtaining useful feedback from Hall of Mirrors (my site about reflective practice).

Level 4 Dialogue

Development outcomes

An individual progresses from Level 1, Level 2 and Level 3 with an understanding of the relative capabilities of the tool and themselves across simple and complex tasks, and with the ability to use a tool to improve their own productive capabilities. In Level 4, they develop an understanding of how to use the tool to clarify, enhance and expand their own understanding of wicked tasks. They should develop:

an awareness of the limitations of their own understanding

the ability to elicit, understand, evaluate and integrate diverse perspectives and ideas

the ability to frame and evaluate constructive interactions with the tool

a degree of comfort with re-evaluating their approach, opinions and ideas

the ability to engage in reflection and evaluation on a process in the midst of that process (reflection-in-action)

Process

The individual is given a highly-complex, ambiguous and disputed task (wicked problem).

They reflect on their existing awareness and understanding of the task and attempt to identify areas where that needs to be improved.

Based on this, they define an approach for the tool to take as a discussion/reflection partner and initiate the interaction.

They reflect on the tool output (question, prompt, challenge) and evaluate whether it has led to a change in their understanding (receptive reflection).

If their understanding has not changed, they consider how they might respond to the tool’s output and evaluate whether that process has led to a change in understanding (expressive reflection).

If their understanding has changed through either receptive or expressive reflection, they evaluate whether that change is sufficient to enable them to progress with the task or whether they should continue the interaction.

If neither receptive nor expressive reflection has changed their understanding, they reflect on the current approach and decide whether to continue or to try something different.

If they choose to continue, they input their response to the tool and repeat the cycle, otherwise they select a different approach and initiate a different interaction with the tool.

Figure 6. Level 4 Dialogue (David Winter)

Inputs

Task requirements

The task should be one that benefits from considering a range of perspectives and alternative approaches. The brief may include information on approaches that have not been successful previously.

Possible approaches

More inexperienced users may need suggestions for possible approaches for the tool to take and roles for it to play in the interaction.

Reflection and Commentary

(by Nick Potkalitsky)

David Winter’s Typology of Assistive Tool Use offers something rare in the current landscape of AI discourse: a patient, structured, and developmental approach to the question of how humans can and should engage with assistive tools. Rather than centering on optimization or productivity shortcuts, Winter’s typology is deeply concerned with the relationship between user and tool — a relationship that evolves as the user grows in awareness, capability, and confidence.

What stands out across all four levels is the emphasis on reflective, intentional practice. Whether working transactionally to generate outputs at Level 1, or engaging in transformative dialogue at Level 4, Winter’s model insists that the user remains an active participant in the process. This is not a vision of passive reliance on AI, nor of outsourcing cognitive labor wholesale. Instead, the typology outlines a vision of shared agency, in which the user develops and exercises judgment about when and how to rely on the tool — and when and how to challenge and extend their own thinking.

Equally important is the model’s flexibility. The existence of both bottom-up and top-down pathways acknowledges that users arrive at assistive cognition from different starting points and with different needs. Novices may need careful scaffolding to progress beyond transactional engagements, while experienced users may leverage AI to shake loose entrenched assumptions and explore new directions. In both cases, Winter provides a clear conceptual map for navigating these journeys.

As AI tools become increasingly ubiquitous and sophisticated, there is growing urgency to think carefully about how we work alongside them. Winter’s typology offers a language and framework for doing just that. It does not prescribe answers, but instead invites us to engage — critically, reflectively, and dialogically — with the opportunities and challenges assistive cognition presents.

This longform post has aimed to faithfully present David Winter’s model in his own terms, while offering context and reflection on why such an approach matters now. In future writing, I hope to continue exploring the practical applications of this typology and to examine how it might inform real-world practices in fields ranging from education and research to creative and professional work.

Nick Potkalitsky, Ph.D.

Check out some of our favorite Substacks:

Mike Kentz’s AI EduPathways: Insights from one of our most insightful, creative, and eloquent AI educators in the business!!!

Terry Underwood’s Learning to Read, Reading to Learn: The most penetrating investigation of the intersections between compositional theory, literacy studies, and AI on the internet!!!

Suzi’s When Life Gives You AI: An cutting-edge exploration of the intersection among computer science, neuroscience, and philosophy

Alejandro Piad Morffis’s Mostly Harmless Ideas: Unmatched investigations into coding, machine learning, computational theory, and practical AI applications

Michael Woudenberg’s Polymathic Being: Polymathic wisdom brought to you every Sunday morning with your first cup of coffee

Rob Nelson’s AI Log: Incredibly deep and insightful essay about AI’s impact on higher ed, society, and culture.

Michael Spencer’s AI Supremacy: The most comprehensive and current analysis of AI news and trends, featuring numerous intriguing guest posts

Daniel Bashir’s The Gradient Podcast: The top interviews with leading AI experts, researchers, developers, and linguists.

Daniel Nest’s Why Try AI?: The most amazing updates on AI tools and techniques

Riccardo Vocca’s The Intelligent Friend: An intriguing examination of the diverse ways AI is transforming our lives and the world around us.

Jason Gulya’s The AI Edventure: An important exploration of cutting edge innovations in AI-responsive curriculum and pedagogy.

TATU -- "...from seeing it primarily as a means of generating outputs, to engaging with it as a critical friend and collaborative thinking partner."

This entire "spectrum" is the antithesis of learning. "...from having a machine do the learning for you to pretending the machine is your imaginary friend who is doing the learning for you."

Working on a machine that works with students is just another way to continue to neglect our cultural responsibilities, just another way to escape our humanity.

There is no reason for large Language Model Generative Artificial Intelligence to be in the classroom.

Outstanding work! Thank you so much for sharing.