Developing a "Conscious" Gen AI Writing Practice

The Vital Connection Between Sentence Composition and Knowledge Constitution

“Scholars Illuminating Texts in Style of 1950s Magazine,” Image Generated by Midjourny

Writing: Foundational for Human Growth and Development

For thousands of years, human beings have used writing as a powerful tool for developing ideas, working through complex problems, organizing large sets of data, communicating important messages, creating new kinds of artistic expression, and exploring internal states of representation.

The rise of large language models have not fundamentally changed this situation–writing is still a critical practice for human growth and development. And yet the presence of this new technology has fundamentally altered the methods and processes through which humans generate written content, begging the question:

How will these human experiences–although not exclusively dependent upon written expression and yet definitely extended and enriched through its practice–change accordingly?

Gen AI Has Changed the Nature of Writing Irrevocably

In a recent post, “The Shape of the Shadow of The Thing,”

accurately describes the near future (perhaps, several months from now) when some powerful AI tool combines existing writing, research, vision, hearing, and speech capabilities in order to serve as “a personal assistant, intern, and companion - answering emails, giving advice, paying attention to the world around you — in a way that makes the Siris and Alexas of the world look prehistoric.”With such tools at human disposal, large swaths of writing that used to consume entire work days will be shrunk down into much more manageable and efficient tasks–potentially opening up more time for more creative work or human-to-human contact, depending upon which optimist AI analyst one asks on a particular day.

The extent to which these writing projects are distributed between more pedestrian or utilitarian tasks and those that require much more analytical and critical thought power is largely a function of where the new large language models go next in their capabilities.

Gen AI Writing: Knowledge Creation vs. Knowledge Synthesis

On the one hand, those computer scientists and engineers working inside the big tech companies–as

has admirably reported in an important series of posts in late August and early September–either truly believe that their tools do have higher reasoning capabilities at the level of AGI or regard such positioning as good for business moving forward.On the other hand, a wide array of different academician on Daniel Bashir’s excellent podcast,

, strongly argue that there are fundamental differences between the kinds of cognition evident in these new machines vs. human cognition. Most recently, Tal Linzen of New York University argued that what appears to be high-level reasoning is in many cases just a function of large pre-training data sets. On the surface, models appear to be solving problems, but beneath the surface, models are simply reproducing solutions already present in their data sets.But what opportunities do humans miss when they outsource more complicated forms of writing focused on developing ideas, solving complex problems, generating creative or unique solutions, and reflecting on or internalizing self-representations?

The Future of Gen AI Writing Is Very Promising

Here, one might say that arguably the same processes still unfold, but this time in harmony with a computational system.

from Cyborgs Writing is developing a cutting-edge AI-infused writing practice. In a recent post, “How I Created a 40-Minute Keynote Using GPT,” Cummings describes a process through which he takes existing text and engages ChatGPT Code Generator in a 3-hour dialogue in order to produce a passabe draft, before giving the text a final edit.The complexity of decision-making, the sophisticated attention to voice and style, and the variegated utilization of text generation as knowledge-refinement are a testament to Cumming’s many years of experience as a teacher, writer, and student of language as well as his abilities to maximize professional and educational benefits from these new technologies.

Requirements for a Constructive Gen AI Writing Practice

More broadly, Cumming’s video is clear evidence that an ethical, engaged, knowledge-generating writing practice can develop between person and machine, if the right conditions are in place: a good teacher (Cummings as his own instructor), a good software, a good textual inputs, an extended time period, a overall plan for the final draft, a developing rhetorical competence, a working knowledge of how LLM respond to particular prompts, a willingness to experiment, a willinging to continue to write “on top of” AI-generated content, etc.

What Are the Psychological and Cognitive Impacts of Gen AI Writing?

And yet, this method of writing is still very new and relatively untested in terms of long-term cognitive benefits and more immediately in relation to its knowledge-constituting capacity both at the internal level of psychological experience and at the external level of new field-changing insights.

Educational researchers, psycholinguists, neuroscientists, and psychologists are all asking the question: Does writing through large language models possess the same knowledge-constituting capacity as more traditional forms of writing for millennia?

The question is of the greatest consequence. If humans shift to a new form of writing and cut themselves off from a core knowledge-constituting capacity, what might that mean for humanity several generations hence?

Educational Research on Writing to Learn

Since the late 1970s, educational research on writing’s impact on learning has passed through three distinctive, but ultimately interrelated, phases. In the 1970s through 1990s, educational scholars developed a highly influential research program focused on Writing to Learn (WTL). In the 1990s through 2010s, the conversation broadened to include programmatic analysis of Writing Across the Curriculum (WAC). More recently, the scholarly discourse has taken a more rhetorical and narrative turn through an interdisciplinary effort to explore Writing as Communication (WAC).

At each phase in this ongoing analysis, educational researchers have argued that writing plays an important, if not fundamental role, in humans’ efforts to work through complex problems, memorize large data sets, synthesize distinctive points of view, and reflect on their process of learning and cognition.

Writing to Learn as Cognitive Stimulation and Knowledge-Constitution

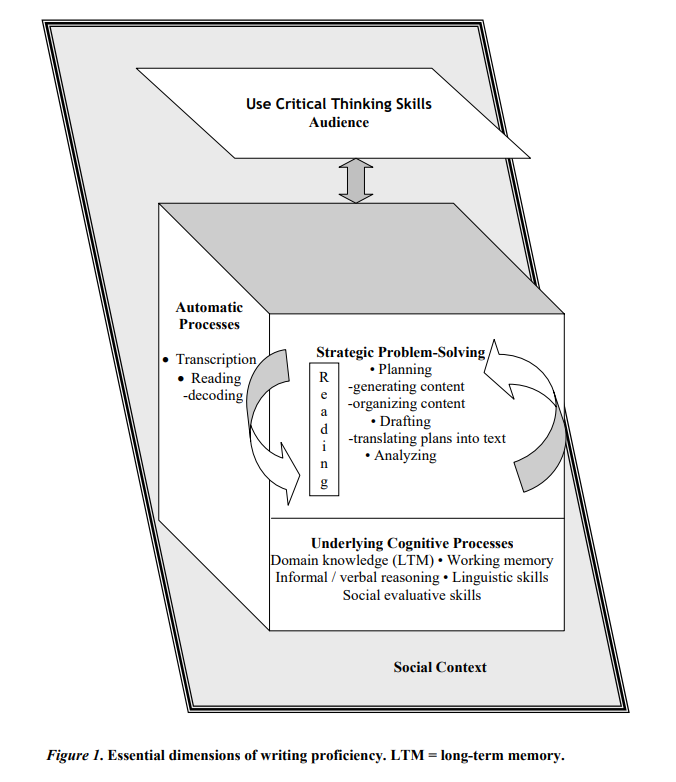

Scholarship from the Writing to Learn tradition demonstrates a high level of sophistication and creativity in the 1990s when researchers like David Galbraith and Mark Torrance synthesized decades of insights from experimental studies into diverse writing practices with findings from the then newly emergent fields of neuroscience and cognitive science.

In an important study, “Writing as a Knowledge-Constituting Process” (1999) David Galbraith revises existing cognitive descriptions of the processes at work throughout the writing process. Up to this point, most Writing to Learn scholars regarded learning associated with writing-in-progress as occurring early on in the process during the stages of memory work and data processing. But Galbraith argues, building on earlier conceptions of Elbow (1973) and Wason (1980) and in light of his own extensive experiments, that learning during writing unfolds through a “dual drafting” process.

“Writing as the Architecture of a Brainstorm,” Generated by Midjourney

2 Stages of Learning: Sentence Generation Is the Most Important Stage

“First learning” takes place through memory work and data processing as the writer plans writing and juggles initial preparatory tasks between short- and long-term memory.

“Second learning,” which Galbraith and other scholars operating in this tradition regard as the more substantial knowledge-constitutive phase, then occurs through the process of drafting, editing, and revising.

Galbraith, citing then emergent research into the nature of memory and cognition, argues that “first” and “second learning” encode knowledge differently in the brain, with the writing process “finishing” and “polishing” the nascent learning products of the “first learning” experience.

3 Major Takeaways from Cognitive-Educational Writing Theory

Galbraith’s writing on learning as writing is highly compelling on a number of levels.

(1) Using cognitive research, he convincingly argues that knowledge is encoded into the memory and the mind more generally in very different ways at each stage in the writing-as-learning process. This qualitative difference matters in the context of AI because if humans turn too much of their writing process over to autonomous agents, they risk missing out on this knowledge-constitutive aspect.

(2) Galbraith cites the locus of sentence-generation as the primary performative center where knowledge-constitution unfolds and becomes new learning. As he observes, “Novel propositions are formed by the sentence production process which operates on the more basic subpropositional level of representation.” As most promises about increased work efficiency and productivity hinge on AI’s supervision or even total control over sentence-level text-generation, human risks prematurely foreclosing this text-specific, cognitive domain that gives rise to novel propositions unless current AI practices are “consciously” adapted to make space for more imaginative work and unassisted drafting.

(3) His writing anticipates the careful design of cognitive processes that eventually emerged in AI large language models (LLMs), with the exception that LLMs primarily learn through reading, whereas human-learning is more evenly distributed across the activities of both reading and learning. Here it is worth restating the problem of causation. AI models, as objects generated through human thought and industry, are becoming mind-like; the human-mind is not becoming more like AI.

In the context of the current debate, Galbraith’s study highlights a critical difference between human and AI autonomous agents. Whereas the core functionalities and capacities of LLMs remain relatively stable throughout writing-as-process, human beings can emerge from the writing experience with increased competencies, capabilities, capaciousness, and resolution to engage in life’s difficult work.

Yes, AI can “learning from examples,” and yet, most AI experts when pressed still shy away from using the actual word “learning” when describing these cases. By contrast, since the origins of writing, humans have charactized the experience of writing as one of problem-solving, knowledge-generating, and discovery:

E. M. Forster’s, ‘How can I know what I think until I see what I say’

Developing a “Conscious” Gen AI Writing Practice

More traditional modes of writing will always coexist with AI-infused modes of expression to the extent that users will still need to fill in prompts with original text or use original text as the basis for AI generative process. In these contexts, writers will need to evaluate proportionality of generative AI use in light of the nature of specific tasks, genres, functions, and purposes.

What kinds of writing tasks can be turned over to generative AI processes? What kinds of writing need more human supervision or need to be written in an entirely unassisted way?

The difficulty of the matter is that we probably will not be able to know ahead of time in an a priori or axiomatic sense which writing tasks will be truly knowledge-constituting and which will not be. Even the most perfunctory piece of writing under the right conditions has the possibility of yielding a dramatic insight if not from a field-changing perspective, then at the very least from an internal psychological perspective. Except perhaps… We all can fill in that blank.

Certainly, the solution here is not to hide from generative AI or avoid using it as a writing tool. Instead, what I suggest is that we think very carefully about what might be lost and what might be gained by using AI in particular cases.

What proportion of our work do we want to turn over to AI? (Here, the questions of volition and choice are critical.) What proportion do we want to retain? Where in the writing process do we feel like we generate the most original thoughts or creative insights? What steps do we need to create a writing practice that is knowledge-constituting?

What Is Coming up Next on Educating AI?

Much of the conversation on Substack about the use of generative AI as a writing tool focuses on persons who already know how to write. In my next post, I will shift my focus to students who are still in the process of gaining reading and writing skills and competencies.

In this different context, the above conversation will follow a similar shape but will have different and much more pressing consequences, entailing more concerted responses on the part of teachers, administrators, parents, and students themselves as each figures out who to best integrate and implement AI into today’s classrooms.

Thanks for reading Educating AI?

Nick Potkalitsky Ph.D.

Check out some of my other articles

An exploration of the human-machine network as the foundation of SEL curriculum

A characterization of prompt engineering as a rhetorical exercise focused on analysis of task, style, and audience

An exploration of in-context learning and “temperature” setting

A characterization of higher ed’s near total silence about student use of LLMs for college applications as setting an implicit curricular agenda for K-12

A “grabbag” of tools, methods, and resources for educators new to LLMs and in search of a way forward…

Thanks for the shoutout! Obviously, to write well still requires writing, even with AI. We can drive anywhere we want to be, but many of us still walk and run!

I do believe that college students can learn many things about writing using AI. Students learn the most when collaborating with each other on writing. With the right mindset, this can be true when collaborating with AI.

Thanks for the restack! I really appreciate that I have found another writer and researcher dedicated to maximizing the educational potential of Gen AI.